Suckin’ Gas?

Biofuels Industry Plans to Alter Consumption Patterns

Biofuels Industry Plans to Alter Consumption Patterns

By Ronald Sitton

LITTLE ROCK, ARK. -- While gas prices climb as spring arrives, green energy enthusiasts wonder about the possible effects on the budding biofuels industry.

In Little Rock, Go Green Biofuels sits just off Interstate 630 at 8th and Chester. Customers must plan if they want to stop since 8th Street operates as a one-way; it requires some drivers to make a loop around the block.

Yet more people consciously make the effort each month since the store opened last fall, according to owner and manager C.E. “Buddy” Rawls. Each time a new customer pulls in, Rawls comes out to greet them and answer questions about biofuels. He uses a pamphlet to convince people that it’s OK to use ethanol in their automobiles.

Go Green Biofuels provides two kinds of fuels: B-20, which includes 20 percent biodiesel, and E-10, a blend of 10 percent ethanol and 90 percent unleaded gasoline. For individuals wishing to completely get off the petroleum, Rawls plans to add B-99 and diesel conversion kits.

Carter Malloy, a Green Circle Biofuels consultant who works with Rawls on expanding his environment-friendly business concept, claims the major problem with biofuels lies with consumer education. He notes most people do not remember the last place they filled up with fuel because of the convenience of fueling stations.

“People have never even had to think about what goes in their gas tank,” he says. “They don’t want to think about it, and they don’t want to think about where they’re getting it. All they want to think about is if it’s 2 cents cheaper or not. That has been the mentality for so long that it is probably for us, on a retail level, that is our most formidable opponent is consumer education.”

Addicted to Oil

But as more people pay attention, a growing number of Americans say the United States needs oil rehab.

A UPI/Zogby Interactive survey found nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of Americans say the United States consumes too much energy, and 63 percent say the Bush administration does not have an energy policy to meet the nation’s future needs. Uncertainty over fluctuations in future gas prices made 55 percent say they want increased government funding for the research and development of alternative fuels. Nearly half (47 percent) of the 6,909 online respondents expect gas prices to increase this year and 11 percent say they think it will rise by more than $1 a gallon. The nationwide survey from Jan. 16-18 carries a margin of error of +/- 1.2 percentage points.

President George W. Bush’s State of the Union address calls for expanded biodiesel use, continued investments into new ethanol production methods and a 20 percent reduction in gasoline usage by 2017. He says he wants to increase domestic production of renewable and alterative fuels so that the United States will annually make at least 35 billion gallons within 10 years.

The 110th Congress seems to be taking note, too, by supporting legislation to develop more renewable energy:

- House and Senate resolutions call for a national renewable energy goal of creating 25 percent of the nation’s energy supply from renewable sources by 2025

- The Renewable Fuels and Energy Independence Promotion Act would create a permanent 51 cent-per-gallon ethanol tax credit and a 10-cent per gallon small producer ethanol credit, extend the 54 cent-per-gallon ethanol import tariff and permanently extend the $1 per gallon biodiesel tax credit and the 10 cent-per-gallon biodiesel producer income tax credit. It sits in the House Committee on Ways and Means.

- The Independence from Oil with Agriculture Act would make permanent certain tax incentives for alternative energy and amend the Clean Air Act to accelerate the use of renewable fuels. It sits in both the House Committee on Ways and Means, and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce.

- The Biofuels Security Act would promote renewable fuel and energy security in the United States. One version sits in the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, while another sits in the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.

- The American Fuels Act would promote the national security and stability of the U.S. economy by reducing the dependence of the United States on oil through the use of alternative fuels and new technology. It sits in the Senate Committee on Finance.

- The National Fuels Initiative would modify credits for alcohol and alternative fuels, amend the Clean Air Act to promote the installation of E-85 ethanol fuel pumps and amend title 49 of the U.S. Code to require the manufacture of dual-fueled automobiles. It sits in the Senate Committee on Finance.

- The Cellulosic Ethanol Development and Implementation Act would require the Secretary of Energy to provide grants to eligible entities to carry out research, development and demonstration projects of cellulosic ethanol and construct infrastructure that enables retail gas stations to dispense cellulosic ethanol for vehicle fuel to reduce the consumption of petroleum-based fuel. The Senate version sits in the Committee on Environment and Public Works while the House version sits in the House Subcommittee on Energy and Environment.

- The Energy Diplomacy and Security Act would increase cooperation on energy issues between the U.S. government and foreign governments and entities in order to secure the strategic and economic interests of the United States. It currently sits in the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

- The Rural Opportunities Act would promote local and regional support for sustainable bioenergy and biobased products to support the future of farming, forestry and land management, and to develop and support local bioenergy, biobased products and food systems. It sits in the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry.

- The House passed the Creating Long-Term Energy Alternatives for the Nation Act by a vote of 264-163 on Jan. 18, a bill that would repeal nearly $14 billion in tax breaks for oil and natural gas companies and put that money toward renewable fuels and energy efficiency programs.

Currently sitting on their respective energy committees in Congress, Sen. Blanche Lincoln and Rep. Mike Ross push the idea that biofuels are good for not only the nation, but the state, too. Lincoln calls Arkansas “critically positioned” to supply biofuels and pushed for tax breaks for companies developing biodiesel plants. In his second year on the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Ross spent a lot of time on energy-related legislation in 2006 by co-sponsoring bills ranging from a strategic refinery reserve to alternative fuel mandates for 2010.

But which biofuel represents the most benefits for the nation and the state?

Ethanol

Critics of Bush’s State of the Union address claim the only way to meet his outlined proposals rests with increasing ethanol production. At first glance, statistics suggest the fuel provides great promise:

- U.S. ethanol production increased from 175 million barrels in 1980 to an estimated 5 billion in 2006, according to the Renewable Fuels Association.

- Ethanol averages 89 octane, about the same as mid-grade gasoline.

- According to drivingethanol.org, modern car warranties allow for using fuel enriched with up to 10 percent ethanol (E-10), which leaves fewer deposits in the engine and eliminates the need for alcohol-based de-icers in winter months.

- Ethanol reduces tailpipe emissions and air pollution by 30 percent since it burns cleaner because it contains more oxygen, according to brochures Rawls distributes from drivingethanol.org. Cities with air-pollution problems require the use of oxygenated fuels like ethanol-enriched gasoline in warmer months in what’s called the “summer blend.”

- A U.S. Department of Energy study suggests using E-10 reduced emissions by 7.8 million tons in 2005.

- A May 2005 report by the Consumer Federation of America suggests drivers could save as much as 8 cents per gallon if petroleum marketers would simply blend ethanol into more gasoline.

According to the Renewable Fuels Association, 110 ethanol biorefineries operate in 19 states with a capacity to produce more than 5.3 billion gallons of ethanol, an increase of 1 billion gallons from the beginning of 2006. In addition, the association said 63 ethanol biorefineries and eight expansion projects are set to come online in the next 18 months that will add nearly 5.4 billion gallons of new production capacity.

In February, Arkansas Farmers Biofuels proposed building an estimated $164 million plant in Pine Bluff that would use corn to produce ethanol. According to the Associated Press, the facility would potentially produce 100 million gallons of ethanol annually, provide 50 jobs for the area and open by harvest season in 2008.

Yet some detractors claim the emphasis on ethanol as the primary alternative fuel under consideration could hurt the nation. Currently, ethanol production relies on corn crops; the annual yield consumes 12 to 15 percent of the nation’s crop.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture projects distilleries will require 60 million tons of corn to make ethanol from the 2008 harvest. But the Earth Policy Institute estimates distilleries will need more than twice as much – 139 million tons – which could lead to a competition for grain and increased price levels.

Enthusiasts argue ethanol production from corn represents a first-generation technology that will likely be exceeded in the coming decade. While corn ethanol only represents a 40 percent increase in available energy, cellulosic ethanol promises at least a yield of five gallons of fuel for every gallon used in production.

Researchers at the University of Arkansas at Monticello have been studying the conversion of biomass into fuel in a joint project including Potlatch, Winrock International and the state Department of Economic Development’s Energy Office. Matt Pelkki, UAM’s associate professor of Forest Economics, notes current technologies exist to convert biomass into cellulosic ethanol, which can be used in a diverse range of automotive fuels and chemicals.

“The Germans in World War II made gas and diesel from potatoes after we bombed their refineries,” he says. “This is basically the same process Potlatch is investigating to create synthetic crude, but the process is cleaner than 60 years ago.”

According to Pelkki, an industrial biorefinery would heat wood waste in a low-atmosphere environment. Instead of burning, the lack of oxygen allows the waste to liquefy at 500 degrees Celsius, producing an oily substance called pyrolysis tar that contains similar properties to crude oil. When heated to 1,500 degrees Celsius, it turns into a hydrogen gas that can be condensed into a biocrude oil and converted to gas or diesel fuel. The professor says biocrude from cellulosic materials can be processed in any oil refinery next to crude oil pumped from the ground.

|

| Photo by Todd Kelley |

| Studying the future -- The University of Arkansas at Monticello's Matt Pelkki says biofuels provide just part of the answer, along with conservation, better fuel economy and reduction in use. |

The industrial-sized biorefinery Pelkki describes would cost an estimated $150 million to build. A DOE grant should help defray costs so construction on the first U.S. industrial facility could begin within two years. After that, he expects to see several of these facilities in the United States.

Arkansas’ five paper mills collect large amounts of biomass and are interested in turning their waste into something useful, Pelkki says, noting the biorefinery concept needs 1,000 tons of biomass each day. Between forestry waste and agricultural waste – including cotton stalks, corn husks, rice straw and poultry litter – Pelkki estimates the state could produce 300 million gallons of gas annually, about a fifth of the total transportation needs of the state, with current technology.

Rawls notes the Canadian company Iogen currently runs a cellulosic ethanol production facility near Ottawa, which produces ethanol from feed stalks other than corn. Chris Benson, director of energy programs for the Arkansas Energy Office, says the state boasts a variety of biomass that could replace corn.

“We have an abundant biomass resource from accumulated agricultural residuals, agricultural waste, crop wastes, timber slash and residue chicken litter,” Benson says. “Arkansas produces about 30 million dry tons of biomass per year, which puts us in the top 10 states in the country.”

A recent report by the Arkansas Natural Resources Commission suggests Arkansas could also benefit from the introduction of a biomass crop such as switchgrass, which produces a high rate of biomass per unit area and as much as 30 percent more biomass per unit water consumed.

Former gubernatorial candidate Rod Bryan suggests hemp or kenaf could be used as a renewable biomass resource. He claims their use would improve the Arkansas economy and lessen dependence upon crops that require heavy subsidization, over-irrigation and ever-increasing pesticide use.

But in the Sept. 22, 2006, issue of Science magazine, Fayetteville’s University of Arkansas researchers call for ecological studies on crops with biofuel potential before putting these crops into large-scale production. Although the crops seem benign, they can spread to other fields where they aren’t wanted, e.g. Johnson grass now is seen as a noxious weed where once it was considered safe to transplant.

Even if cellulosic ethanol produces fuel quantities exceeding current projections, a lack of infrastructure could hinder its distribution. According to the Federal Trade Commission’s 2006 Report on Ethanol Market Concentration, ethanol providers only increased nationwide from 75 in 2005 to 90 by mid-October 2006. The FTC estimates 110 firms will be operating facilities by the end of 2007.

This presents problems for government agencies like the General Services Administration. Bobby Dukes manages the GSA’s federal fleet and is trying to meet former President Bill Clinton’s mandate that 75 percent of federal vehicles be flex-fuel capable by 2009. Flex-fuel vehicles can run on E-85, which contains 15 percent ethanol.

Since it’s a federal agency, Dukes says the GSA is required to buy ethanol if it’s available. While 1,000 E-85 retail outlets exist in the nation, Arkansas does not have one. Only two of the state’s stations sell E-10: Go Green Biofuels and the Almyra Farmer’s Association’s co-op outside Stuttgart, which first started selling ethanol in September 2005.

Dukes says Arkansas’ federal fleet currently includes more than 40 percent of flex-fuel vehicles – approximately 400-500 sedans, 200 minivans and 150 trucks – since starting on the mandate in 2000. He says federal employees are not mandated to go out of the way to get 10 percent ethanol if it’s not available in their area. When they can get it, ethanol cuts into gas mileage; e.g. Dukes notes some federal sedans on gas average 23 miles per gallon on the highway, but will only average 19 miles per gallon on E-10.

“(Ethanol) burns faster and cleaner, but the mileage is cut down,” he says. “It’s just cutting a few miles off your range; that won’t hurt us any.”

Rawls notes gas efficiency decreases even more when using E-85. In hopes of alleviating that problem, the DOE announced in late January that it would support engineering advances to improve the fuel economy of E-85 engines and reduce vehicle emissions.

Brooks Davis, a member of the Almyra Farmer’s Association’s board of directors, said the co-op receives pure ethanol from Missouri on a train, then blends it into E-10 for the pump. The additional freight costs keep ethanol near $3 a gallon in Stuttgart.

“It sold pretty good at first, but not as good now that ethanol price is higher than gas,” Davis said.

State Agriculture Secretary Richard Bell told the House Agriculture, Forestry and Economic Development Committee in mid-January that Arkansas will have a chance to break into the ethanol market later, when technology allows the gasoline substitute to be made from wood products. For now, Bell suggests the state should concentrate on developing biodiesel.

Biodiesel

The National Biodiesel Board generally defines biodiesel as a domestic, renewable fuel for diesel engines derived from natural oils that meet the American Society of Testing and Materials’ specifications. Biodiesel comes from soybean oils, cottonseed oils, fish oils, and rendered poultry or animal fat, which produces an oil similar to soybean oil when cooked down.

Biodiesel can be used in any concentration with petroleum-based diesel fuel in existing diesel engines with little or no modification. The blend determines the name, e.g. B-2 indicates the fuel contains 2 percent biodiesel, while B-100 represents pure biodiesel.

Assuming biodiesel growth reaches 650 million gallons of annual production by 2015, the NBB projects America’s biodiesel industry will create 39,102 jobs and add $24 billion to the U.S. economy between 2005 and 2015. The board notes 88 plants in the nation produced an estimated 200-250 million gallons of biodiesel in 2006, which tripled the 2005 production of 75 million gallons.

Two biodiesel plants currently operate in Arkansas. Beginning production in 2005, FutureFuel Corp. produces about 9 million gallons a year at the former Eastman Chemical Co. plant southeast of Batesville. The London Financial times reported Oct. 16 that parent company Viceroy Acquisition Corp. plans to increase FutureFuel’s production to 196 million gallons a year by April 2008, and distribute the biodiesel through Apex Oil of St. Louis.

Stuttgart’s Patriot Biofuels started production in April 2006 and produces 3 million gallons a year with plans to increase to 10 million gallons a year. Cal McCastlain, Patriot Biofuels’ secretary and general counsel, estimates Arkansas’ annual capacity of 25 million gallons of B-100 could yield between $62.5 million and $75 million to the economy, money that would otherwise go out of state.

“We’re not just producing for in-state consumption but also outside Arkansas to other regional markets that we can access by highway, rail or water,” he says. “It’s not out of reason for us to have 100 million gallons annual production capacity. Most of that production would be sent outside the state to other markets.”

Other plans call for biodiesel production facilities around the state comprising:

- a 6-million-gallon facility including a grain-handling facility, soy crush plant and soy meal mill on a 22-acre tract along U.S. 165 south of DeWitt. Arkansas SoyEnergy Group announced its plans last September.

- a 10-million-gallon facility in the Little Rock Port Authority on the Arkansas River. Green Way Bio Energy announced its plans last September.

- a 10-million-gallon facility in Crossett’s industrial park on U.S. 82 east of town. Ashley County’s Pinnacle Biofuels announced its plans last September.

- a 30-million-gallon facility with an integrated soybean extraction in Pine Bluff’s Harbor Industrial District. Delta Intermodal and Bioenergy Co. announced its plans last August to work with Arkansas River Regional Intermodal Authority, the city of Pine Bluff and Jefferson County to develop, construct and operate the facility.

- a 40-million-gallon facility south of Helena-West Helena on Arkansas 20. Planters Service and Sales Inc. announced plans in September for a new business, Delta American Fuels, to build and operate the facility.

A managing partner in Arkansas SoyEnergy Group, Jon Hornbeck owns Hornbeck Seed Company of DeWitt and Worldwide Soy Technology biotech-research company. He plans for his new facility to provide a market for local soybean growers.

Hornbeck claims soy-oil-based biofuels provide one of the better quality sources of B-100. Though the SoyEnergy Group plant will not begin production until late summer or early fall, he anticipates expanding from 3 million gallons at start-up to producing 7 million gallons in two-to-three years based on supply and demand.

“I believe the demand for biodiesel in our area, an agricultural market, is strong,” Hornbeck says. “The farmers want home-grown energy. My plant will fulfill the needs of my area of the state.”

McCastlain says the diesel market in Arkansas is currently near 1 billion gallons annually, with one-third off-road agricultural use and about two-thirds highway use in trucks and busses. In order to fully exploit the potential, McCastlain said the distribution network must be able to receive and blend biodiesel into petroleum diesel.

Biodiesel blenders receive a federal tax credit of $1 a gallon for pure biodiesel. Stan Jorgenson, an engineer for Engineering Compliance and Construction Inc. who’s also on the board of the Arkansas Environmental Federation, said a study funded by the DOE resulted in two biodiesel-blending facilities in North Little Rock: Arkansas Terminating and Trading and HWRT Oil Co. HWRT upgraded its terminal to become the first in the state to offer biodiesel and ethanol blends in the same place. The terminal provides B-2, B-5, B-10 and B-20 to diesel distributors through a rack system, which allows truckers to key in the blend needed in their tanker.

“We want biodiesel at all of those terminals to make distribution of biofuel even easier,” McCastlain says. “We want all of these guys to handle biodiesel whether mechanically blending or splash blending. The costs at each facility depend on what the facility does. For a distribution network to be effective, we’ve got to have distributors capable of receiving B-100 year around and blending it into their local fuel supply.”

Detractors voice concern that biodiesel could affect soybean prices like ethanol’s effect on corn prices. McCastlain notes higher corn prices increased soybean prices, which increases the price of soybean oil and raises the price of animal fats. At the same time, oil and diesel prices dropped.

“That’s good for consumers and the transportation industry, but biofuels producers are looking for stability in the market and looking to see how things shake out,” he says. “The products we make (biofuels), the products we use (raw materials) and the products we compete against (petroleum fuels) are all commodities and commodity markets by nature are susceptible to significant price movement -- sometimes good, sometimes bad.”

McCastlain says 2006 marked a watershed year with the market responding to biofuels. Speculators took interest in the market’s movement and played the financial standpoints. The new demand increased volatility, which resulted in higher grain prices for both livestock and biodiesel producers.

The current price movement may strain biofuels producers, but McCastlain notes markets for both raw materials and finished products are not fully accustomed to incorporating biofuels into the market moods. As the markets grow accustomed to incorporating biofuels’ demand into the price discovery, McCastlain says volatility will lessen, leaving less room for speculators. Regardless, he does not foresee direct competition with human food.

“I do not fear a dilemma between fuel or food,” he says. “I think as the commodity prices go up, it impacts the net profits of the biofuel producer. That will slow down the frenzy to build biodiesel plants that we saw in 2006.”

Steve Bolin, president of Pinnacle Biofuels Inc., says the Crossett facility is currently under construction. He says he expects to open in June and provide 12 jobs at the production plant with a $500,000 to $600,000 payroll while producing 10 million gallons of biodiesel annually.

Pinnacle Biofuels will use chicken fat oil, cottonseed oil, palm oil and soybean oil in its biodiesel. It also will feature a blending station and a pump to supply biodiesel. Bolin says the company sits near a new railroad spur that will allow feedstocks to be shipped in and biodiesel to be shipped out by rail.

While he plans to sell most of the company’s biodiesel to a major oil company, Bolin says Pinnacle Biofuels will probably distribute 2-3 million gallons annually in South Arkansas. Several pumping station owners in South Arkansas have already shown interest in supplying the biodiesel, he says. Though feedstock prices continue to rise, Bolin says he believes his alternative feedstocks will keep costs bearable.

“We’re too far in the game to turn back now,” he says. “We’re moving straight ahead.”

Another potential pitfall for biodiesel can be directly attributed to winter weather. Attendees at Arkansas State University’s 13th annual agribusiness conference in mid-February heard about biodiesel gelling when it turned cold last October. FutureFuel’s manager of research and development indicated the mandated shift to “ultra-low sulfur” diesel caused problems with biodiesel blends. But with help from the National Biodiesel Board, biodiesel producers adjusted their processing to take ultra-low-sulfur diesel into account.

Ann Hines, executive vice president of the Arkansas Oil Marketer’s Association, says approximately one-third of the association’s members sell biodiesel. Some reported B-100 gelling this winter, causing unanticipated costs to buy heated tanks to successfully handle the product. Hines notes only four companies in the state install the heated tanks.

“This is our first year of experience with this product,” Hines says. “We’re all learning. My people are working closely with the companies buying from us to get solutions to the problems, but it’s not going to happen tomorrow. Although the weather may warm up and we won’t need them.”

Steve Danforth, a principle in Agri-Process Innovations – an engineering company that builds biodiesel plants – and Patriot Biofuels, says employment at his Stuttgart fabrication company increased from 10 to 50 employees since May 2006. Danforth is currently working with state legislators on House Bill 1379 and Senate Bill 237.

HB 1379 would create an alternative fuels development program and fund. Danforth says the proposed three-part $20 million incentives package would provide grants for additional feedstock producing plants, blending locations with heated tanks and biofuels plants. The state House of Representatives already approved HB 1379, which will cover the supply side of the biofuels industry, Danforth says; however, he says SB 237, which would cover the demand side, is currently receiving resistance from the Oil Marketer’s Association.

SB 237 proposes to develop the alternative fuels industry in the state by establishing goals for alternative fuels production and setting standards for the quality of alternative fuels and the percentage of alternative fuels in diesel fuels. If passed, every gallon of diesel sold in Arkansas after July 1, 2008 would contain at least 2 percent biodiesel; a year later, the minimum would be 5 percent biodiesel.

McCastlain claims Arkansas’ two current biodiesel plants could meet the needs if the state required retailers to sell B-2. But if retailers started selling the common commercial blend of B-5, McCastlain said the state will need additional capacity to produce the 50,000 gallons of biodiesel needed.

“I don’t think anybody in the industry is expecting to replace petroleum as a transportation fuel, but it is a reasonable goal to expect biofuels to be a very significant supplement,” he says.

Both bills went before the Senate Agricultural Committee Feb. 27. Danforth says HB 1379 is meeting no resistance, but at this point he only gives SB 237 a 50 percent chance of becoming law. He says both bills must pass if Arkansas plans to become the “Silicon Valley of biofuels.”

“If that dream is to come true, we must start to support the biodiesel industry here in the state,” he says. “If we don’t support the biodiesel industry now, it’s going to be hard to convince investors that Arkansas is the place to invest their alternative fuel dollars.”

According to the United Soybean Board, the number of fuel suppliers and other retailers offering soy biodiesel jumped from around 450 in the fall of 2002 to over 3,000 in 2005. The USB notes biodiesel sales totaled 15 million gallons per year in 2002 and exceeded 75 million gallons in 2005. The U.S. Department of Energy has forecasted sales to reach as high as 1.2 billion gallons a year in the next decade.

| Biodiesel can be obtained in 23 Arkansas counties -- Arkansas Farm Bureau |

Hines says 30 biodiesel retail stations exist statewide. While the main market lies with end users in the farming community, she indicates plans call for additional retail-oriented outlets.

Both the Almyra Farmer’s Association’s co-op and GoGreen Biofuels sell biodiesel in addition to ethanol. Davis notes the co-op started pumping biodiesel in March 2003, just days after the state’s first dealer from Harrisburg’s Farmers Supply.

“At the farm co-op we’ll do whatever we can do to get what’s U.S.-grown or U.S.-produced; that’s what we want to do,” Davis says. “We can’t all work at fast-food restaurants. We’re going to need to produce something and do something here and not just have service-related industries. We need to have a manufacturing base here. We don’t need to import everything we got if we want to stay a strong nation. This biofuels is a part of that.”

John Hoffpauer, transportation planner for the regional transportation planning organization Metroplan, says the DOE study that brought biodiesel blending facilities to Central Arkansas could not get the fuel into truck stops along Interstate 40. He says the truck stops face a major expense of installing new storage tanks.

“If (the truck stops) put (biodiesel) in an existing tank and make it available to all trucks, their demand would utilize the entire production in Arkansas,” Hoffpauer says. “Patriot Biofuels could work an entire year and only supply one truck stop in Arkansas. We’re not producing enough to meet the demand of truckers coming through town. We don’t understand the scale of production yet.”

Still, some entities are making the switch to biodiesel.

Barry Beaver, maintenance director for Central Arkansas Transit Association, says CATA’s entire diesel fleet, which includes 19 vans and 57 buses, now runs on about 50,000 gallons of biodiesel every month. The expense of an above-ground tank led Beaver to put biodiesel in both of CATA’s underground tanks.

“It’s just something we went to because we thought it was good for the environment,” he says. “So far it’s doing fine. We don’t have the cold weather and gelling problems that some places have further north.”

CATA serves Little Rock, North Little Rock, Maumelle, Sherwood, Cammack Village and two express buses to Jacksonville. Though CATA keeps its engines well-tuned and in good mechanical shape, Beaver says warranty concerns keep CATA running B-2 or B-5.

Hoffpauer also helps with the federal Clean Cities program, which reimburses school district fleets for incremental costs of using biodiesel. The Little Rock School District and the Pulaski County Special School District began using biodiesel in its buses during the 2004-05 school year. LRSD’s 107 buses consumed 43,000 gallons of B-100 and reported a 1.1 miles per gallon increase in fuel efficiency, while PCSSD’s buses used 14,000 gallons of B-100 and reported a .78 gallon per mile increase. Hoffpauer says $18,000 in a fund is collecting interest while the Clean Cities program waits to get billed.

McCastlain says Arkansas ideally sits in a position to exploit the biodiesel market to the West and East. He expects technological improvements in production processes on par with those in computers and telecommunications. McCastlain says the experiences from the last year will help biodiesel producers provide well-informed input to state legislators developing the state’s biofuels policy.

“Biofuels are no longer an alternative fuel,” he says. “They should be viewed as mainstream because they’re here, we have them. For Arkansas, we should recognize and fully exploit a unique opportunity to be a major production center for biofuels in America. The Natural State is well-positioned to take a lead in the biofuels industry.”

Benson says benefits include not only economical and environmental gains, but also increased national security since biofuels come from local communities. He says the Arkansas Energy Office is working with other stakeholders and legislation sponsors to give incentives to take advantage of the state’s resources.

“I think it means we can start to develop a bioenergy economy that will be extremely important to the state,” Benson said. “It lessens our dependence on petroleum products. We’ll be working our way to this bioenergy technology, but we’ll have to work through different fuels to get to the point where it will make a difference to the state. It’s not going to happen overnight. Patience is needed.”

Though biodiesel promises increased benefits to the state and the environment, Malloy and Rawls plan to give consumers a third alternative. But instead of converting fuel, they plan to convert automobiles.

Straight Vegetable Oil?

“The use of vegetable oils for engine fuels may seem insignificant today. But such oils may become in the course of time as important as petroleum and the coal tar products of the present time.”

Rawls enlisted Malloy’s help so that Go Green Biofuels will soon begin converting diesel-powered vehicles to run on straight vegetable oil. A native of Little Rock, Malloy attended the University of Arkansas and earned a degree in physics. While in Fayetteville, he played guitar and synthesizers in a nationally touring Jazz band that searched for cheaper ways to travel after spending earnings on gas.

|

| Fill ‘er Up -- Carter Malloy fills one of his converted Ford Excursion’s tanks with B-20 biodiesel. |

“We were just blown away with how easy it was and how much money we saved,” he says. “Right off the bat in the first six months, we saved $3,000 to $4,000 in fuel costs.”

The success led Malloy to consider helping others. He convinced Golden Fuel Systems to allow him to start a dealer network in Fayetteville, the first of six now operating in the United States and one in Japan.

GFS continually referred business to Malloy and his partner in Fayetteville, where they converted vehicles using GFS-licensed technology under the name Green Circle Biofuels. Malloy returned to Little Rock six months ago but his partner moved to New York. Malloy now plans to operate the business as a subsidiary of Go Green Biofuels.

According to GFS, the ambient temperature of an engine (160-to-200 degrees) thins the vegetable oil to enable its use in modern diesel injection systems. The conversion system provides a secondary tank for diesel to get the engine up to temperature and unrestricted flow up to the injection system. The Web site Goldenfuelsystems.com notes the laws of thermodynamics and the design of diesel engines make it impossible to inject cold oil into an engine at operating temperature.

The conversion will not work on gasoline engines as vegetable oil and diesel rely on compression for ignition since they’re not as volatile as gasoline. Unlike gas engines, ASE certified diesel mechanic Bryan Wigley notes diesel engines run most efficiently between 200-205 degrees.

Green Circle Biofuels refers to the idea that using vegetable oil as fuel creates a carbon loop unlike petroleum, which when burned releases carbon that’s been underneath the earth for millions of year back into the atmosphere. Malloy claims crops grown by farmers will absorb the same amount of carbon released by burning vegetable oils made from the same crops.

“The emissions practically are zero when you take into account they’re just getting sucked right back down by next crop,” he says. “We’re contributing to our farmers instead of crazy people who want to attack us. So you’ve got domestic policy and homeland security, then you have supporting farmers and helping environmental policy.”

Malloy will help Wigley with the first conversions. According to Goldenfuelsystems.com, the benefits of converting include:

- reduced fuel prices, as many restaurants give away filtered waste vegetable oil. Although the site advises staying away from fast-food restaurants, it recommends visiting independently owned restaurants and notes most Asian restaurants provide a good resource for filtered waste vegetable oil. While the FAQ notes you always need an owner’s permission to get the oil, once obtained you should look for a dark liquid instead of a white cream and be sure to leave the dregs.

- reduced air emissions: vegetable oil burns 50 to 75 percent cleaner than petroleum, and produces 40 percent less soot than diesel.

- longer engine life, though the engine and injection systems still need regular maintenance

- increased power and fuel economy

- a one-year warranty for normal wear and tear of the conversion kit and a 30-day warranty for the 12-volt gathering pump

- a $4,000 federal tax write-off

The kits range from $900 for a small car to $2,000 for a large truck with a large tank, while installation costs $1,200 for a car and $1,500 for a truck. In addition to converting diesel automobiles, Malloy says the company has adapted a semi truck, generators and lift pumps for farmers, and a trackhoe that’s getting a few more hours per tank than it once did.

“If you’re a guy who drives to work and the post office and home each day, it may not be the most financially plausible thing for you to do,” Malloy says. “But if you’re a guy that drives to work, or somebody who drives 20,000 to 30,000 miles a year versus someone who’s only averaging 12,000, then it can start to make sense financially really fast.”

Rudolph Diesel’s first engines built in the late 19th century ran on plant oils, but were converted to run on petro-based “diesel” fuel following his death. Malloy holds few illusions about why most diesel owners would consider switching back to vegetable oil.

“Frankly when I got in the business, I expected that our customer base was going to be young progressive people looking to do good for the planet,” he says. “What I found quickly was that those people wanted to save a buck. Granted, a lot of them have environmental goals as well. Either way, knowingly or unknowingly, they’re contributing to the environment.”

If Malloy represents a converter, master carpenter Grady Ford and his 1984 Ford Pickup represent the converted.

Ford estimates he spent nearly $3,000 working with his mechanic on weekends to convert his diesel truck to burn vegetable oil using information he found on the Internet. He says it would have cost less if a network had existed to consult when various problems arose. He first started running vegetable oil in his diesel engine last spring on his daily downtown commute.

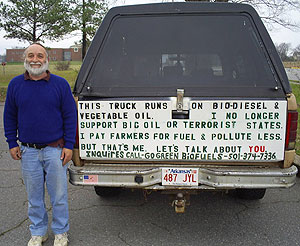

|

| The Converted -- Since putting this sign on the back of his converted diesel truck, Grady Ford has seen everything from people passing, braking, reading the sign and giving him a thumbs-up to other people reading his sign at a stoplight, putting their eyes down and passing him. “I kept it clean; there’s nothing insulting on it unless you take it that way. Before I put (Rawls’) number on there, it was a political statement, now it’s a commercial.” |

Since the conversion, Ford says his truck gets more than 15 miles per gallon on the highway. He changes his fuel filter once a year because he occasionally drives on dirt roads. Ford accidentally put diesel into the vegetable oil tank once; he drove to Memphis without any problems. He claims his truck runs quieter on vegetable oil than on diesel and he’s happy with the power, noting his truck pushed a Bronco up the hill when his friend’s fuel pump went out.

The U.S. government does not recognize vegetable oil as a fuel, so no official government studies exist though private companies have conducted their own tests. Malloy says anecdotal evidence suggests using vegetable oil as fuel increases engine life, efficiency and power. He estimates between 8,000 and 12,000 U.S. automobiles run on straight vegetable oil.

In warmer temperatures, any diesel engine easily runs on vegetable oil only as ambient heat from the engine thins the oil enough to allow it to shoot through fuel injectors. When temperatures turn colder, a manual switch allows the driver to go from the oil to diesel or biodiesel and back as needed to clean the injectors or keep the fuel lines from filling with congealed vegetable oil.

Ford plugs in a block heater during colder nights that keeps the engine temperature between 100 to 120 degrees, so the engine will start the next morning on vegetable oil if needed. His only problem came when the heater didn’t work one night; he had to wait three hours the next morning to get going.

“But that was the cold part of this winter,” Ford says. “I’ve got a 23-year-old truck; it doesn’t want to start on diesel fuel when it’s cold.”

Wigley notes diesel also gels at lower temperature, but better-designed fuel systems keep the fuel lines closer to the engine so the radiant heat from the compression chamber keeps the fuel warm. Rawls notes B-100 gels at about 38-to-42 degrees. Historic temperatures in Little Rock would allow conversions to run on standard vegetable oil or B-100 in any diesel engine from April until a cold snap in mid-to-late October.

Wigley says most diesel engine problems stem from air or fuel restrictions. He once repaired a converted engine where the owner changed a fuel filter but forgot to remove the o-rings, a piece of which fell and restricted the fuel flow. Another owner forgot to switch the valve and the line filled with cold vegetable oil.

Malloy suggests regular maintenance, including changing the secondary fuel filter that filters the vegetable oil. Controlling the input quality determines the frequency of the filter changes. Wigley says it’s cheaper than changing the fuel filter in a regular diesel every time the oil is changed.

Conversion means converting mindsets, too. It’s not yet possible to pull up to just any station and get used vegetable oil. Malloy and Bryan occasionally gather used vegetable oil from local restaurants for their converted vehicles. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. restaurants produce about 300 million gallons of waste cooking oil annually.

Ford buys five-gallon containers of new vegetable oil each week. Ford says he wanted to make sure any problems with his conversion were mechanical, not the fuel, which he drains in a few minutes from the containers into his car with the aid of gravity.

“I haven’t saved a thing because I’ve been buying the fuel,” he says. “It costs me about $3 a gallon for new oil at Sam’s. But then again I only use 10-to-15 gallons a week. That’s why I call myself an enthusiast; I ain’t saving nothin’.”

Malloy returns to the biodiesel versus vegetable oil argument, i.e. mixing chemicals versus heat. While chemicals provide a convenient method, he says it’s more environmentally friendly to use heat but “convenient-centric” Americans want things as easy and as trouble-free as possible.

“It comes down to how much do you want to get involved? I would say owning a Prius versus owning a vegetable car is low involvement versus high involvement,” Malloy says. “With the Prius, you have all the same convenience you’ve always had. With the vegetable oil car, you have the option of adding a lot of work by going out and gathering your fuel. We currently are trying to get away from gathering mentality to a convenience mentality. We want people to be able to come and fill up just as easily on vegetable oil as they would on any other type of fuel.”

|

| Agent of Change -- Go Green Biofuels owner "Buddy" Rawls hopes to turn the station into a Green destination. |

Rawls wants people to think of Go Green Biofuels as Arkansas’ green destination and a home base for green-related matters of concern. He envisions a convenience store featuring organic-based foods and other sustainably based products and services. With Malloy’s help, Rawls says he plans to fine-tune the concept then replicate it through franchising opportunities.

Malloy says venture capitalists are looking for opportunities in the environmental energy field, but few entry points exist for entrepreneur who may have a few hundred thousand dollars to spend.

“You can buy a $50 million processing plant or spend $70 million to start up a solar company, but you can’t just get in it on the consumer-to-consumer level or the business-to-consumer level,” he says. “We’re hoping to create just one of those opportunities. We also anticipate there’ll be plenty more in the future as the consumer mentality changes.”

Green Circle Biofuels would not be a part of the franchising concept, as Rawls wants to keep the conversion work centrally located. He says two customers recently inquired about possible conversions, which will be scheduled by appointment.

Currently, Rawls is working with Patriot Biofuels to provide B-99 and with Malloy to provide used vegetable oil collection service. Malloy expects the factory spun used oil to sell for $1.50 to $1.75 a gallon. After finding electronic pricing signs too expensive, Rawls found a flip mechanical sign to put the pricing on the canopy; it’s on his to-do list.

Kevin Jacobs will open KJs Auto, Tire and Wheel (http://kjsautotireandwheel.com) in Rawls’ garage. In business since 2004, he specializes in custom wheels, tires and accessories including window tinting and vinyl graphics. Jacobs also plans to offer nitrogen, which he says is used in tires by both NASCAR and the airline industry.

“It’s been used forever,” Jacob says. “You’ll get better fuel mileage and your tires will last longer. A slow leak will become no leak.”

Although Jacobs may do some mechanic work, he does not plan to perform major motor work. However, his work in the garage will allow Rawls to open from 7:30 a.m. to 6 p.m., which should allow more drivers to stop at more convenient hours. He says business keeps improving and he knows a lot of people who make the loop back to his store.

Rawls says more than 30 people have signed a petition asking the city to turn 8th Street back into a two-way to make it easier for customers to make an impulse buy. While he’s working with the city, he says it could be a question of cost.

He seems prepared to do whatever it takes to tout the benefits of a biofuels industry and Arkansas’ place in it.

“I believe alternative fuels are the future,” Rawls says. “We must become independent. More people will see the benefits and support biofuels. Nothing would please me more than to have a chain of biofuel stations around the state. It seems a dream at this point, but it’s certainly something I’d like to see happen.”

Only 14 percent of the listed Biodiesel distributors in Arkansas do not carry all grades of biofuel, from B2-B100.

http://www.biodiesel.org/buyingbiodiesel/distributors/showstate.asp?st=AR

Only 7 percent of the listed biodiesel retail locations in Arkansas carry all grades of biofuel, from B2-B100.

http://www.biodiesel.org/buyingbiodiesel/retailfuelingsites/showstate.asp?st=AR

For more information on converting diesel engines to run vegetable oil

http://www.goldenfuelsystems.com/resources_faq_systems.php

This article orginally appeared in the March 2007 Little Rock Free Press.