Training To Be An Astronaut By Brian Griffin Illustrated by Christopher Bookout When Father left me standing on the roof of the new house, three stories off the ground, I quickly realized that this was another opportunity for some astronaut training. Why, I asked myself, should I waste my time nailing shingles to a roof? After all, wasn't Neil Armstrong himself out there somewhere, at that very moment, practicing for his heroic trip to the moon?

Here are the most important rules of the astronaut corps — keep your head clear, keep your sights focused, and keep calm no matter how tough things get. That's why astronauts have electrodes all over their bodies. Mission Control monitors their vital signs constantly, because an astronaut has to remain calm in tough situations. So I scooted as close as I could to the edge of the roof and forced myself to stand erect, inching forward until my toes were hanging over the eave; then I closed my eyes, extended my arms to either side, and focused on slowing my heartbeat.

Now that I've entered college I still react that way to girls. I don't know why. Toeing the edge of the roof that day was, by comparison, a piece of cake. There I was, 30 feet above the ground, playing chicken with gravity and practicing heart-rate control — arms extended, eyes closed, thinking calm, calm, calm. And sure enough, after a while I could feel it — the calm overtaking me, the hypnotic summer sounds of mockingbirds and droning bees and the warmth itself receding to some place in the back of my mind. I stood somewhere outside my body, totally alone. All the world had been reduced to the sound of my own breath, the movement of air, the filling of space. And then, after what seemed like a long while, someone tapped me on the shoulder and said, "Dude." I didn't expect it. I inhaled quickly and felt myself lunge upward, and my arms flew forward in an arc, and I sensed my body launching into the air. But something held me back — a single arm across my chest. I sprawled backward onto the shingles and opened my eyes, and in the sun's glare I made out a blonde-haired, blue-eyed guy beside me. He wore jeans, combat boots, no shirt. His hair was long and curly, his skin deeply tanned. And oddly enough, he looked not at me but at the landscape — at what was left of the old farm where we were building our house. After a while he spit a glob of saliva over the edge of the roof, then glanced at me. "So," he said. "What the hell's wrong with you?" I shrugged. "Nothing," I said. "I was, like, training. To be an astronaut. You know." He grunted and looked at the landscape. "Well. I guess I ought to be right proud to meet you, then," he said, still looking away. His voice was low and very slow. "My name's Webb." He grinned, almost a grimace. "I'm training to be a member of the planet earth." He looked at me, grinned quickly again, then grew somber. There was a long silence. It was almost like he was waiting for me to reach out, to take his hand. Finally he walked a few feet away, scratched his crotch, and began nailing shingles to the roof. And he nailed steadily all day long. I scrambled along with him, working more efficiently than I ever had before. For some reason I felt I had to prove to this guy that I was at least as good a worker as he was — and at the same time, somewhere deep inside myself, I resented his intrusion into my space. About all I could get out of him the entire day was that Father had hired him to help with the roof. He wouldn't say much else.

"Yeah, party. Come on. Let's have a little fun." He put his hands in his pockets, hunched his shoulders, and jerked his head toward the woods behind us. "Out at my place." And then he looked in my eyes and leaned close, so close I could smell his breath like some kind of dead something, and in a low voice he said, "I got these chicks, man. I got these really good-looking chicks." He grinned and winked one bloodshot eye. I looked at the woods and then over my shoulder at Father, who went inside the house. "I don't know," I said. "I've things to do." "Come on, man," he said. "What are you, some kind of pussy?" I didn't reply, so he said, "Yeah, that's it. You're some kind of candy-ass pussy." It occurred to me that this was the first time Webb had ever spoken to me about anything other than roofing. And of course, at that time in my life I was not accustomed to such raw language. But somehow I knew I'd been challenged. And I was perfectly aware that accepting such a challenge might not be wise. But we learn from our mistakes, so that one day, we will obliterate all possibility of their occurence — something an astronaut must work toward. Just let me say this: If a billion years ago some ancestral fish hadn't crept from the primordial soup of an ancient sea into the alien terrestrial landscape, if he hadn't taken a chance, the human race would not exist. Without alien worlds to dare into and conquer, we get stagnant, like water behind a dam Besides, I was interested in meeting girls. So I fell in behind him as he crossed our yard. I said, "Okay, okay, I'll come along, for a while anyway. Perhaps you can get me a date with one of those girls you mentioned." He stopped when I said that. We were at the edge of our property, right where the thick undergrowth began. He turned to look at me. "A date?" He grinned and said, "I like you, man. I mean, really." Then he laughed. "A date." He turned, pushing through high weeds, and stepped onto a small footpath hidden behind some honeysuckle. I followed him into the woods. At that Point all I knew about Webb was what Father had told me on the very first day. After Webb had gone home, I said, "Where'd he come from Father? Where'd you find him?" "Who?" said Father. He was counting bundles of shingles, his lips moving silently as he counted. "That Webb fellow." Father shrugged. "He's one of the Dentons," he said. "And he's one of the good ones, too. Like his daddy was — Hamp Denton. Good Christian people, salt of the earth." I nodded. Father knew most everybody out here in this part of the county. It's where he grew up. He pulled a slip of paper from his pocket and wrote something on it, then ran his fingers through his silver hair. "You know, Hamp Denton went to war, and fought in it," he said. He looked off into the woods. "No prissing around feeling sorry for himself. Soldiers were soldiers back then. And it's the same with his boys. You could learn a thing or two from Webb, son. About work. About pulling your own weight in this world." I didn't say anything. "They're not all like that," said Father. "Many of the Dentons are trash. But Webb, he's one of the good ones." I hoped so. The whole reason for building a house in the country was to be around "the good ones" of the world. That was the whole idea. Life in the suburbs had finally got to be too much for Father. The riots downtown, the traffic jams, noisy neighbors — he couldn't take it anymore. The final straw was when the government threatened to bus kids from downtown Chattanooga to our schools in East Ridge, bringing inner-city troublemakers to our community and taking kids like me to those bombed-out schools downtown. The very week the busing plan hit the papers, Father bought land in the country — one acre of a huge, abandoned farm at Bucktooth Haven, a few miles north of Chattanooga, near Hixson, Father's hometown. The land had seemed secluded enough, and quite peaceful. It was alongside a road that had been built for access to the new nuclear power plant, which was under construction about a mile away — a convenient location, really, since Father worked there in public relations. One morning back in the winter, when we were still framing the walls of our new house, we found that a truckload of insulation had been ripped to shreds. I hate to use the word," Father told me, "but those niggers did that." "Really?" "Yeah. There's a bunch of 'em out here, son. You'll see them in little shanties if you go down the new road here and take a right on Maloney. Now, they're good folks, mostly, don't get me wrong — coloreds here in the country aren't like those downtown. But there's a bad apple everywhere, I guess, and these days some people aren't satisfied with what life hands them." "Yes sir." "Don't go down there, son. Stay away from Maloney Road." "Yes sir, Father." Father called the County Sheriff's office and convinced a patrolman, who was a relative of ours, to drive by Maloney Road and hand those people a warning, and that was the end of that. Things went smoothly from then on. Time passed, summer came, and soon I forgot all about it. "I made this trail myself," Webb said. "You know how?" "How?" I asked absently. We were only a few steps into the woods behind the house, just over the property line. I was still wearing my tool-apron, jammed full of roofing nails. Webb stepped behind a cedar, then jumped quickly back onto the trail and spun toward me. He had a sword in his hands. He held it high above his head and lunged at me, giving a yell that matched the way his eyes looked — suddenly wild, stabbing and hard like shards of ice. I guess I backed up or something, but I don't remember for sure; all I remember is falling backward, flat on my butt, and then trying to raise my feet into the air, as though that would stop him from doing whatever he was about to do. But my feet were tangled in something. I couldn't lift them. Webb swung the sword above me. It made a sound like the wings of a bird hovering above water. I tried again to lift my feet, and I felt something digging tight into my left ankle, sharp and tight. I looked down and saw a strand of barbed wire, scabbed with rust, tangled around me. Nails were scattered across the leaves. Webb stood over me, swinging the sword, fast now, in tight loops like the turns of a maple seed falling to the ground, bringing it so close I could feel air moving on my sweat, cool and soft. Then he stopped, lowered the sword, and laughed. "Yeah," said Webb. "Pretty good, huh? I made the path myself. With this sword." He laughed again. "And you know, this sword is really old. I wonder how many heads got chopped with it, in its day." He ran his finger long the blade thoughtfully. Suddenly he swung at a dogwood limb, severing it cleanly with one blow. He laughed, then looked at me. "Aw, man, scared the bejesus out of you, didn't I?" He reached down and took my arm, helping me up. "Sorry, Dude. Didn't mean anything by it." "I wasn't scared," I said. I wiped my forehead with the sleeve of my shirt. "Not really." I bent down and extracted my ankles from the barbed wire. There were small punctures on the shin of my left leg. "Then come on, Dude," Webb said. He turned and walked along the path again, swinging the sword at foliage. I hesitated. "I'm not sure coming with you now would be a good idea," I said. "Maybe some other time." "Not a good idea?" "Yeah, you know. Not wise. Not smart. Not prudent." "Oh. Oh, yeah. Prudent." He laughed. "Prudence is dead, man." He began singing, "Dear Prudence, won't you come out to play?" Then for no apparent reason he seemed suddenly angry, swinging the sword wildly into the tall weeds and saplings. "Come on, man. What's wrong? You chicken? You some kind of pussy?"

And that's when the girl appeared. That's the only word for it — she simply appeared, as though she had been there all along but only now had suddenly decided to reflect light. She was tall, tanned, muscular looking, wearing small pink shorts and a halter top. She was on the trail between Webb and me, but Webb didn't see her. I watched her chase after Webb and jump on his back. She giggled, her arms draped over his shoulders, her legs around his waist. Webb dropped the sword and started spinning around. She covered his eyes with her hands. She's still giggling, her teeth flashing, her eyes like light. His face is distorted and red as he spins, bumping into trees and stumbling through weeds, and she's laughing and he's spinning, clearly not laughing, until finally he buckles his knees and leans backward, dropping her onto her back in the weeds. Then he turns over and grabs her wrists, pinning her to the ground, and he's laughing now. And they kiss. A long, sloppy one. Finally he lets her up, both of them red-faced and sweaty, and it's like I'm not even there — she laughs again and jabs him in the belly and takes off down the trail, and he scrambles up, grabs the sword, and takes off after her, out of sight. And for no clear reason, I followed. Then I met another girl. She was standing alone in sunlight, about ten feet from me, where the trail opened into the clearing near the barn. Her arms rested on top of an old fence post; she balanced herself there with one leg stretched high into the air, toes pointed like a ballerina. Her head was held back, her face to the sky, in profile. She seemed chiseled there in the bright sunlight of the clearing, like a delicate swath of sculpted wood. And the biggest surprise was that, except for a small pair of cut-off jeans, she was naked. "Hi," she said, without looking at me. Then she began moving her leg methodically, down, then up, then down again. "You must be Walter." She lowered her leg, turned slightly, and began with the other leg. "I'm Iris," she said. Again she tilted her face toward the sky, as though there was something there nobody else could see. After a moment she stopped her exercise and turned to face me. Her eyes were green and very bright, and there were beads of perspiration on her forehead. "Webb said you were coming," she said. She took two steps forward, then bent at the waist and touched her toes, keeping her knees locked. "He says you're stupid," she said. She stood straight again and looked at me, expressionless. "Are you?" I said nothing. There were freckles on her face, and her hair, pulled back in a ponytail, was a sandy-red, dusty color. Strands of it had pulled free of the ponytail, falling across her forehead. Her cheeks were flushed from exercise. I looked at her breasts. "Do you dance?" she asked. "No. That is, yes." "I dance quite a lot," she said, matter-of-factly. We were silent as she continued her exercise. I stared, but she ignored me. After a while she pulled on a T-shirt and started across the clearing. "Come with me," she said.

That's one of my weaknesses, I guess — my tendency to follow beautiful women. If I'm to be an astronaut, that's something I'll have to work on. After about a quarter of a mile the road topped a hill, and there was this old guy in the road, looking into the woods, his hands in his overalls' pockets. He doesn't seem to notice us. "Hi, Pops," says Iris as she passes him. He says nothing, doesn't move. When I pass, I notice he's glassy-eyed, looking lost, like someone waiting on a bus in an unfamiliar neighborhood. Unlaced boots, no shirt; one leg of his overalls is cut just below the knee, jagged and stringy, as though tailored with an axe; the other pant's leg is much too long, dragging the ground. After I pass him, he yells, "Hey!" I look back. He's still staring into the woods. "Hey!" he says to the trees in a painful, strained voice. "Them cattle! Them cattle's jumping higher than I ever seen cattle jump." He laughs. "Don't run away, now! Don't run away." I look at Iris. She's walking, still very fast, ignoring me and the old man. So I continue, watching the sway of her hips. The road curves, and I look back one last time. The old man is still standing there, staring into the woods, smiling now. Around the curve is a tar-paper shack. The road ends there, in a big mud clearing without a speck of grass. There's a broken-down tractor, a wrecked Packard with a tree growing through the windshield, a rusty trash barrel with wisps of smoke coming from it. A typical Bucktooth Haven house. Iris just marches right up to the cabin and opens the door, and at this Point I'm thinking about Third World training — the way they take astronauts to places like, say, the Polynesian Islands, or maybe Africa or Mexico, so they can teach them how to survive in remote, backward places. After all, one day the astronauts may re-enter the atmosphere on Emergency Trajectory, splash down in some remote place, and wash up on the wrong continent. Anything could happen to an astronaut. Iris stands in a beam of late evening sun in the open door, watching me. Her hair is loose now, her pink face floating in a mass of hair, bright and weightless. I look in her eyes and she turns away, and I follow her into the blackness of the cabin. The room is windowless and dark and there is a strangely pungent odor in the air. I hear a television, but the sound is garbled. Then I see the TV across the room, flashing a pale blue glow into smoky air. It's John Wayne as an infantryman, leading GIs across a beach, goading them to their deaths with his heavy, furrowed stare. The door slams behind me. I spin around and there's Webb's face stuck right in mine, his big toothy grin floating disembodied in the darkness like a moon; smoke streams from his nose and from his smile, his skin pale blue from TV glow. "Well," he says. "Well, well, well. It's little Walter." He moves beside me, puts his arm around my shoulder, and leads me toward the center of the room. "Tell me, Walter," he says. "Do you like it here?" "Where? Right here?" "Bucktooth Haven, dumb ass. How do you like Bucktooth Haven? I mean, so far." "Oh, just fine. It's nice here." "Well, don't worry, it'll grow on you." I heard a girl laugh. In the darkness I could make out a sofa beside the television. Webb's girlfriend sat on the sofa, right in the middle of it. Oddly, the television faced the center of the room; anyone sitting on the sofa could not see it. He says it's nice here," she said, laughing some more. "Come here, Walter. Come over here. Sit by me." She patted the sofa. "Come." "Go on, Walter," said Webb. "Sit by Jane. Jane wants you to sit by her." "Come," she said. "Don't be bashful." "Go on, Walter." "Right now, Walter." I walked to the sofa and sat beside her. She put her arm around my shoulder. "Relax, Walter. Relax." She laughed again. "Webb tells me you're going to be an astronaut." She put a cigarette to her lips, inhaled deeply, then extended it to me. "Here," she said, in a strained voice, holding the cigarette in front of my face. "Try this." I noticed she was not exhaling the smoke. She was obviously trying to hold it in as long as possible. I looked carefully at the cigarette. "Is that a marijuana cigarette?" I said, watching smoke snake from it, wrapping around her fingers in graceful curls. "No offense, Jane, but I really shouldn't participate in smoking marijuana cigarettes. Really. It wouldn't be wise." She spewed all the smoke from her lungs at once and began laughing. Webb was laughing too. He was on the floor in front of the sofa, lying on his back, laughing, and it went on for what seemed like forever, until Jane finally got her composure enough to say, "Pretty please, Walter. Just one little puff?" I said, "No thank you. Seriously. I can't tell you how important it is that I remain drug-free." And they both went into more hysterics. I felt deeply embarrassed. I tried to rise from the sofa, but Jane kept her arm around my shoulder, and said, "Please, Walter. Please stay." So I leaned back, and she pulled herself closer to me, and the room grew quiet. The only sound was gunfire, garbled and frantic, from the TV set. It sent strange flashes of light across the room, which, as best as I could tell, was full of cardboard boxes. "Well!" I said, as cheerfully as I could. Suddenly Webb stood over me. "Take the joint, Walter," he said. "Take it." I just looked at him. "You think I'm joking?" He snickered. "Come on, you coward." He seemed serious now. Jane held the joint in my face again. I noticed her fingernails. They were very long, a pink color, with a different colored star on each one. I looked at Jane's face. It was all but hidden behind her long, blonde hair. Then came the sword, the tip of it. Webb held it against my nose, right between the nostrils. I leaned my head back against the sofa as he pressed the sword firmly against my skin. "Take the joint," he said. I could smell the sword, a deep, cold smell, like a well. "Take it. Now." Jane snickered and said, "Forget it, Webb. He's out of it." "I said take it!" He was yelling now. I reached out, but I didn't know where the joint was. All I could see was the sword, the long, silver trail of it. It pushed harder against my skin, painful now. I flailed blindly into the air. "Take it!" Then a hand appeared and gently brushed the sword aside. I let out a long sigh and saw Iris's face floating in the murky dimness of the room, a calm face — expressionless, radiant, like a white cloud against a thunderhead. She sat on my lap, and I could feel the pulse of her, the warmth of her as she moved her mouth close to mine, pursing her lips into a red, wet O. She placed the joint there — backwards inside her mouth, with the fire side in — leaving a bit of it protruding from her lips. She closed her eyes, moved closer, and blew. Jane laughed and said, "Suck, Walter, suck!" Iris's arms were around me, her lips against mine. She ran her fingers in circles across my earlobes. Smoke filled my nostrils. My mouth flew open and smoke filled it, too. My vital signs grew chaotic. "Shotgun!" yelled Webb, laughing. "Go for it, Dude." Iris's hands were in my hair now, running through it gently. The smoke was like some living thing passing between us, and that moment seemed to go on forever. But in just a few seconds I was coughing uncontrollably. Iris raised up, pulled my head to her breast, and held me there, and I coughed for a long, long time, with tears running down my face. I could hear Webb and Jane laughing, and the mangled voice of John Wayne droning on and on, and I could hear Webb saying "Go for it, Walter, go for it." But Webb seemed far away, in some other world. After a while, the front door opened and the room was flooded with light, and my body went tense. It was an adult — the old man, the one we'd passed on the road — and Iris didn't even move from my lap. "Hi, Pops," said Iris, brightly. She took a long drag on the joint, and passed it to Webb, who was leaning on the arm of the sofa beside us. "Granddad," Webb said. "I'd like you to meet Walter, an astronaut. Walter, my grandfather, Hiram Denton, also an astronaut." The girls began laughing. "I'm not an astronaut at all, Mr. Denton. But I'm glad to meet you, sir." They laughed at that, too. "Isn't he modest?" said Webb. He inhaled from the joint, which was tiny now, then dropped it to the floor. He went over to Mr. Denton, still in the doorway. "Look," Webb said, holding the palm of his hand in front of the old man's face. "Hey diddle, diddle," he said, Pointing as though reading from his palm. "The cat," he said slowly. "And the fiddle." Mr. Denton's eyes were fixed intently on Webb's palm. Jane was laughing again. But Iris quietly rose from my lap and crossed the room. "The cow," said Webb. Then he dropped his hand and put his arm around Mr. Denton's shoulder. "The cow. What about the cow, Pops? Tell us about the cow." "It's gonna rain," said the old man, his voice thin, wheezy. "And there's so much to do." "Pops," said Iris. She took his hand. "Come with me. Your dinner's ready." But Webb kept his arm around the old man. "No, wait. Tell us about the cow. Walter wants to hear about the cow." I shrugged. "If Mr. Denton would rather eat his dinner . . . ." "Shut up," said Webb. "The cow, Pops." The old man looked at me. "Them cattle," said the old man slowly. "They jump. Up." He looked at the ceiling, one hand rising into the air. "Higher than you'd believe, just soaring into the sky. Up. Up. And away." His arm moved from side to side, as though wiping the room away. Jane began laughing uncontrollably on the sofa next to me. She stretched her legs across my lap, covering her eyes with her arm as she laughed, on and on and on. Webb looked at me and pointed his thumb at the old man. "He's a trip," said Webb. He laughed. "Ain't he a trip?" "Come," said Iris, her face as expressionless as her voice. She led the old man to another room. "He's my ticket from 'Nam, that's what he is," said Webb. Jane kept laughing, holding her belly now, but suddenly Webb wasn't laughing at all. He was squatting in the doorway, face in his hands, staring at the floor. After a while I stepped quietly past him, into the sunlight. "I guess I have to go now," I said. "Later, Dude." Webb didn't look up. "Sure," I replied. I looked back into the room. Jane seemed to be sleeping, stretched on the sofa. The TV showed President Nixon now. He stood in front of a map, Pointing at it with a baton, talking urgently. Little B-52 bombers were pasted to the map. "My regards to Iris," I said. No one replied. I found my own way home. When I arrived home at sunset, a formal table was set in the dining room, with a white cloth and brass candelabra. This came as a surprise, because the house was not yet finished and we were still spending the nights at our place in the suburbs. "Walter, please wash and come to table," said Mother. She and Father were already eating Chinese take-out. "Yes Ma'am," I replied. Wash cloths and towels were hanging neatly in the bathroom, which still had a plywood floor. When I returned they passed food to me in silence. Then Mother said, "Well, Walter. You can explain everything now." "Now Wanda, leave the boy alone." She ignored him. "Walter?" "I've been at Webb's, Mother. We . . . " "See, Wanda, he's been with Webb Denton. Now let the boy be." "Well, I hardly think I'm out of line to ask what they've been doing all this time, am I dear? I mean, really." "They've been hiking in the woods, haven't you, Walter?" "Yes sir." "See? Now let him be." We were silent for a while, listening to the sound of cicadas through the open window. "Did he show you that Mustang?" Father asked. "No sir. I saw an old Packard, but no Mustang." "The Mustang was Mickey's, you know." "Whose?" "Mickey's. His brother. He's been dead three years." "Oh?" "Vietnam." "Oh." "What I like about them Dentons," Father said, forking out more noodles, "is the way they stare tragedy in the face. They've had more than their fair share, but they just stare it down. They're tough. An inspiration, that's what they are." "Yes sir." "They stick together. You meet Hiram?" "Yes sir." "Haven't seen him in years. I been meaning to get out there and see him." He reached for another eggroll and bit in to it. "You mean Hiram Denton is still alive?" asked Mother. "Heavens! Pass the soy sauce, please." I passed it to her. "It seems I remember, from years and years ago, a terrible fire involving the Dentons," she said, conversationally. "Yeah, and it was right out back here." Father pointed to the back of the house. "Back in those woods somewhere was the old Denton homeplace. A bunch of Dentons died in that fire. Webb's mom included. This land I bought was a part of their back acreage. Our barn was a Denton barn." "Fascinating," said Mother. "Walter, would you please close the window? There's a draft. You've hardly eaten." "Yes Ma'am." "That boy Webb, he's a good boy," said Father. "I went to school with Webb's daddy, Hamp Denton. He died when Webb was a baby. Stepped on a mine in the jungle at Guadalcanal, four years after the war ended." I pulled the window closed. That's when I noticed the glass was smashed. There was a jagged hole in it, about the size of a pancake. "Now Webb's taking care of his granddad," Father said, "living with him in one of the old sharecropper cabins. And he's no more than nineteen or twenty." "Goodness," said Mother. "He must be quite a boy." "Webb's Uncle Buck looks after them some. He lives in Huntsville, though. You remember Buck, don't you honey?" "Oh, of course I do," said Mother. "Walter, please eat your dinner." "Huntsville?" I asked. "You mean, Alabama?" "Yeah. When Buck retired from the Air Force, he became a businessman. Runs an electronics supply house in Huntsville." "Does he deal with NASA?" NASA, I knew, had a base in Huntsville, near the old Redstone Missile Arsenal. Father looked at me thoughtfully. "Yeah, I guess he does. You know, you might do well to get to know these Dentons, son." He stuffed the rest of the eggroll in his mouth. "A boy like you ought to think of the future."

Jane and Iris, it seemed, were always at the Denton place. And I quickly learned that Webb was something of a comedian; his odd behavior and scary actions had a kind of skewed humor, when viewed from the proper angle. But he was a tangle of mystery, too. The fact is, I couldn't get over the idea that he didn't like me — that he hated me, even. He was volatile, confusing; he carried the sword everywhere, hacking new trails across the old farm. Often he was full of anger, as though the very weeds and saplings that choked the farm were choking him, too. Then he'd be as gentle as a lamb, funnier than somebody on the Ed Sullivan show. Maybe it was the marijuana that made him that way. Webb smoked constantly. And you must understand that, although I joined in those marijuana sessions, it was only as an observer: I didn't inhale. To Webb and his friends, smoking was almost a religion; no one was allowed to turn it down — no one, that is, except Iris. She could do as she pleased. Iris, of course, was the reason I kept going to Webb's. She was distant, though, and even more mysterious than Webb, and I quickly came to realize that she was unattainable — that I could only look. She was always dancing, it seemed, solitary and simple, with an almost weightless grace, floating through woods and fields in wide loops around us while Webb and Jane and I sat together in the sun, the way hippies do, passing the joint among us. There was usually a radio there, too, playing Hendrix, the Stones, that sort of thing. Sometimes Iris would join us in our little circle, sweating, her legs reddened from weed-scrapes, her face covered in a slight, almost inward smile. She'd take a hard drag from the joint and dance away again, her body light like cotton, lofting above the earth like something the planet couldn't convince itself to hold on to. Sometimes I'd roam the woods behind my house, looking for her, utterly devoid of self-control. One day I stepped from one of Webb's trails into a weedy clearing, and there she was 50 feet from me, dancing naked and alone in high grass beside the ruins of an old chimney. I watched for a while, full of longing and a bit of shame at my cowardice, until at last she grew tired, dressed herself, and disappeared quietly into the woods. Webb told different stories about that sword of his. Once he said his father's grandfather had carried it in the Civil War, when he was one of Nathan Bedford Forrest's cavalrymen, defending honor and the Southern way of life. Another time he said his father had picked it off the dead body of a German officer in a trench outside Berlin in 1945, beside a ruined cathedral. "Have you ever been in a cathedral?" I said. We were sitting beneath an apple tree in an abandoned grove. I could see Iris about 50 feet away, balancing on her toes with her arms above her head, hands palm to palm. "What the hell do you think, dumbass?" said Webb. "Of course I've never been in a cathedral. And you haven't either." "They have vaulted ceilings," I said. "Two-dozen stories high, or more. And you know why?" "No," said Webb. "To approximate heaven. Men have always strived for the heavens. The Wright Brothers were just trying to round things off, you know. Trying to fulfill those old dreams." "Now isn't that peachy?" Webb said. He drew on the joint, smiled, and spread his arms wide. "This is my fucking cathedral, man," he said. "You can keep your vaulted ceilings and your rockets." I looked around. Iris was doing pirouettes beneath the apple trees. After a moment she picked an apple, holding it high in the air. Then she fell to her knees and extended the apple before her in both hands, as though it were King Arthur's chalice. Jane smiled, nuzzling against Webb's chest the way a cat would. I half-expected her to start purring. And it was then that I finally realized what idiots these people were. I knew I had no business hanging around with them, and I vowed to try my best to stay away. I knew it would be tough, though. I couldn't get Iris out of my mind. One day in early September, as we were moving our belongings into the new house, Father said, "You seen Webb, lately, son?" "Not in several days, sir." "Did you hear about Iris?" I dropped the box of books I was carrying: Father knows Iris? "Hear about who?" I said. "Iris. Webb's twin sister." My surprise was quickly followed by anger. Why hadn't he mentioned Iris before? Father knew the entire Denton history, but until now he had acted as if she didn't exist. "Oh, her. Iris. No sir, I didn't hear about Iris." Then I blurted out, without thinking, "And this Jane person. Who is she?" "Jane? What are you talking about son?" Father set his box down and looked at me. I kept quiet, so he said, "Listen, son. Buck Denton came by yesterday, on business. He says he took Iris to live with him in Huntsville. For her own good. Took Hiram too. That's all I'm saying. I don't know anybody named Jane." "So Iris lives in Huntsville now?" He looked worried. "Yeah, that's right, son. With her Uncle Buck." He was talking softly now. "Buck, he's having hard times, you know. And Iris, she needs help too. So Buck put her to work. It'll be good for her, son. You know, straighten her out." But I wasn't listening. I was still overwhelmed by the news that Iris was Webb's sister. It cast a new light on everything that had happened. After all, Webb had encouraged the development of a relationship between Iris and me, hadn't he? At least he had led me to her. So if he thought I was so stupid, if he didn't like me, what motive could he possibly have had? What had Webb been up to all this time? Father was giving me a funny look, so I picked up the box and went inside. In a way I was relieved that Iris was gone — what my willpower couldn't accomplish, circumstance had accomplished for me. Father said Webb had refused to move to Huntsville; he was still out in that cabin. But with Iris away, there was no reason for me to deal with Webb any longer. Besides, school was again in session, and I was very busy. So I vowed again to forget about Webb, and to forget Iris, too. In the space age, dwelling on the past is the ultimate folly. So when Father announced that he had finally convinced Webb's Uncle Buck to sell him the rest of the farm, I saw no problem with it. Progress is progress, after all. It's what makes us human. Then, less than three weeks after closing the deal with Buck Denton, Father sold the land to developers from Connecticut at a substantial profit. Soon it was obvious that the developers were planning to build a major subdivision in the overgrown fields behind our house. Surveyors swarmed around for more than two months, taking measurements and putting out a system of fluorescent stakes to mark the boundaries of lots and to show where the roads would go. Men in suits and hardhats marched through the woods carrying large rolls of paper, spreading them out occasionally and talking urgently, Pointing in different directions. Then, in late November, the bulldozers came. Mother convinced Father to build a high fence around the back yard — a wooden privacy fence. "We're using redwood lumber in this fence," Father said. "Real redwood, from California. If you're going to do something, son, it's important to do it well. This fence will last forever." I had my last party with Webb on an unseasonably warm afternoon, late in November. I was on the front porch of our house that afternoon, studying for a physics exam, when Webb drove by in his Mustang convertible. He passed the house, then slammed his brakes and backed up, burning rubber in reverse. Jane was in the passenger's seat. She wore dark glasses, and her hair, very long now, was flying in all directions. "Well, if it isn't Werner Von Braun," he said. "Burn my draft card, Jane, I've decided to become an astronaut."

"Get in, Dude." "Sorry Webb, but I have things to do. Maybe some other time. Besides, your car is a two-seater." Jane stood, then perched on the back of the seat. "Here, Walter," she said, smiling, "sit between my legs." "Get in," said Webb. "Just a short ride. There's something I need to show you." Jane still smiled. When I got in, she wrapped her legs around my shoulders, placing her bare feet in my lap. She wore shorts, her legs bare and stubbly against my cheeks. "Mind if I call you Werner?" Webb said. Jane giggled. The car sat still while Webb gunned the engine. "And now, ladies and gentlemen," he said in a fake German accent. "The Commandant Verner Von Braun will cause two-thirds of the people of the planet to disappear before your very eyes, something we in the party have been working toward for many years." "How?" said Jane. "By strapping them to a V-2, of course. By shooting all the miserable undesirables into the deepest recesses of space." Jane ran her hands across the top of my head. I felt hot, sweating between her thighs. "Or better yet," he said, "Werner will strap himself to the rocket. He'll colonize new worlds. He'll stick his holy head in stellar sand." Webb gunned the engine and the car jerked forward. The tires squealed. Jane tightened her grip as the car accelerated. Webb's laughing now. "How about them G-forces, Walter?" he yells. "Like that? 100! 110! Fast enough for you, Walter?" I close my eyes. Jane is leaning forward, her hair streaming over me, her arms locked around my neck; I feel the pavement end and I open my eyes. The hourglass of the nuclear plant's cooling tower flies toward us; parked trucks, piles of pipes, stacks of lumber fly by as we move in circles around the tower, around and around through a cloud of our own dust, white and acrid, the car bucking and sliding as though the earth itself is pushing against us, Jane clamping her thighs and arms tightly around me, holding hard to me, trembling, screaming something I can't make out, the radio playing "Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts' Club Band" so loud I can't understand what Webb is saying to me. He's yelling, his face contorted in what appears to be uncontrolled rage as the car spins, sliding sideways, the car pulling tighter and closer around the concrete and steel of the cooling tower until we're on the pavement again, gliding, and I sink limp into the seat as the car jerks hard and quick onto one of the new subdivision roads, jolting and jumping through the desolate scrape like the bucking of a mad animal, Jane's screams desperate now, screaming at Webb in anger and fear until at last the car falls to rest. Surveyor's stakes are piled beside a gray tangle of blackberry and pokeweed. Webb gets out of the car. "I gathered them for you, Walter," Webb says. "All for you." He takes a can of gasoline from the car's trunk and douses the stakes. Jane and I stand watching as he throws a match to it and it flames up. "Breaking a few windows, trashing some insulation, that's just kid's stuff," says Webb. "I have so much more to contribute." I stared at the flames and remembered my father warning me about the black folks on Maloney Road. "So you did that, Webb?" I said. "It was you?" "Yeah," he said. He was calm now, smiling, beatific. "I did the insulation thing. Like it? I used the sword, of course. I didn't vandalize, Walter. I carved." "But why? Why did you do it?" "For the same reason I'm burning these stakes, you asshole." He grabbed my arm and looked straight into my eyes. I could feel him trembling. I glanced at Jane, but she quickly looked away. She was as distant as the trees around us. "I mean, hell, what do you expect, man?" Webb's voice rose like a hard wind. For a moment I thought I saw fear in his eyes. I looked at the burning pile of stakes. Flames were inching into the weeds. "Father thought the Negroes did it," I said. "I mean, he thought Negroes vandalized the house." Webb let go of my arm. He seemed to relax. "Yeah, well, the niggers did do it." "But you said . . . " "I did it, the niggers did it. Whatever. It's all the same thing. You see, a man like your father needs his niggers, So I'm his niggers. I see it as my civic duty." Jane put her arms around him from behind. "Somebody's got to do it, Walter." Then I realized his problem. He couldn't see the big picture. I thought of photographs of our globe, blue and alone in the darkness of the universe — the scale of the whole thing. "Look," I said. "What does it matter in the long run? You need a new perspective on things, a new angle. What does this little patch of ground really amount to?" "Space," he said, absently, eyes on the ground. Jane hugged him from behind, rubbing her hands across his chest. "Let's go, Webb," she said. "Come on." I shrugged. "The world's a big place, Webb." Then he suddenly began coughing, a kind of angry, spitting cough, and it took a moment for me to realize that he was actually trying to speak. "Let's go, Webb," said Jane. "Forget it." He pushed her away, but she came back to him. "You think . . ., " he said, "you actually think . . . ." He looked away and laughed one sharp laugh, hard like an icepick through ice, as though everything I've been saying — indeed, everything I am — is so absurd it's impossible for him to reply any further. He shook his head and smiled an angry kind of grimace-smile, shaking his head over and over, saying "Man, man" in a tone of disbelief, shifting his weight from foot to foot, his eyes everywhere but on me. So I turned from him. I walked along the bulldozed scar through the woods, toward two trucks sitting about a hundred feet away. I knew a trail must cross near there, a trail that would lead home. And as I was passing the trucks, I noticed their tires were slashed. I saw Webb's sword there, lying in the dirt. "Pick it up, Walter." Webb had followed me. He pushed me in the small of the back. "Pick it up!" I turned. He was smiling, a nauseating smile. Smoke filled the air behind him. He stepped forward and pushed me again. "There's a good tire left on that GMC," he said. "Pick up the sword, Walter. Slash it. What's wrong? You a pussy?" I could smell smoke. Webb shoved me again, and I stepped backward. He kept coming at me. "Go on, Verner, take the sword. It's just a tire. What good is it? This is the space age!" His eyes were like pits, his sneering lips spread back across yellowed teeth. I was sick of him now. When I took the sword he laughed and slapped me on the back. "Go on, do it," he said. "What's wrong? Think you'll get in trouble, Walter? Hell, you're a fuckin' astronaut! If there's trouble you can just blast off!" I stared at the tire, the mud on it, the gravel stuck in the heavy tread. My eyes were stinging from smoke. I felt anger well up in me, anger at Webb and everything connected with the idea of Webb; anger at the way disrespect and chaos seemed to be what he lived for, revelled in, made a faith of. And he kept pushing me. Clearly I was not in possession of my senses, because what I did then seemed, at the time, inevitable, perfectly normal, even necessary: I yelled at Webb — I don't remember what I yelled, but I yelled — and I jabbed the sword into the tire. It barely made a prick, So I yanked back and jabbed again, throwing my weight into it, feeling it sink into the rubber as I strained to push it deeper. Finally there was a hissing sound as the tire deflated. And instantly I felt like a fool. I heard Jane's nervous laughter as Webb fell to his knees in the dirt and bowed to me, over and over. He, too, began laughing. I tried to pull the sword from the tire, but it wouldn't budge. Jane and Webb walked away, arm in arm, as I pulled uselessly on the sword. Finally I ran along the trail toward home. When I came to the redwood fence at our yard, thick smoke was blowing in the trees. I went through the gate and into the house, and from my bedroom window I watched silent flames move across the overgrown fields of the old farm. Oddly, the fire never touched the barn, even though it burned in the weeds and trees around it for almost twenty-four hours. Our house was saved by volunteer firefighters from Bucktooth Haven. Father got me off the hook entirely. He fixed things with the county police, one of whom was a relative of ours. I didn't even know I was a suspect until a deal was made. It happened on Christmas Eve, three weeks after the fire. It was the same Christmas that Apollo 8 circled the moon. I was in the living room in front of the TV, waiting for the live coverage of the space flight to begin, but I had turned the volume down low because Mother and Father were arguing in the kitchen. I could hear the rise and fall of their voices, but I couldn't make out the words. Bits of tinsel fell from our Christmas tree. A squirrel was hiding in it, scared to come out. He had fallen down the chimney earlier that day. I walked to the front door and turned on the outside light. Raindrops were falling in the darkness, and the ones falling close by, near the light, were shiny white, like little streaks of ice. I crossed the room to the Christmas tree and knelt in front of it, thinking I would try to shoo the squirrel across the room to the open door. I parted the branches of the tree and peered inside. There he sat with his beady eyes and his pulsing throat, perched on a branch at eye level about three feet away. I'd never seen a squirrel so calm before. Usually a squirrel is a bundle of nerves, but this one just sat there, as if being trapped in our alien world brought out the best in him. I had to shake the tree three times before he would budge, and finally he scooted to the end of a branch, jumped to the wall, and scurried up it, freezing dead still in the cobwebs near the molding. I hit the wall with the palms of my hands. The squirrel shifted quickly but held his ground, clinging to the wall mysteriously. Then, as I was about to give up, the squirrel leaped for the open door and floated across the room as if he were weightless, with his legs outstretched like little wings. He floated out into the night, slowly, beautifully, gliding with unbelievable grace into the darkness.

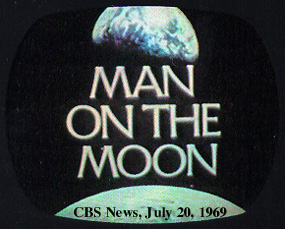

"You're damn lucky your Uncle Manny's with the county police," said Father. "You listening to me, boy?" "Yes, sir." "That Denton boy turns out to be trash after all," Father said. "Trash is trash, and Webb is big pile of trash, and all the worse for acting like he wasn't. I prefer a Denton that acts shiftless and lazy to one that acts like he's really on the ball, only to turn around and fool you. There ain't nothing worse than that." "Yes, sir." The TV was showing the astronauts huddled together, their faces unshaven. The Bible was passed, weightless, from one astronaut to another. We were quiet for a while, with just the astronauts talking. "And God called the dry land Earth," said the astronaut. "And the gathering together of the waters he called seas; and God saw that it was good." He closed the Bible. A toothbrush floated by. "Roger," said Mission Control. "We copy." Just after Christmas I was offered a nice scholarship to the engineering program at M.I.T. — a decent start on my way to the launch pad. The last time I saw Webb was about a week later, on a science club trip to the county prison. Some wiseacre had decided it would be a neat gag to dress in prison garb and get our yearbook picture taken behind razor wire, making little rocks out of big ones. Just before we left, a guard gave us a tour of a cellblock that was supposed to be empty, but there was somebody asleep in a cell at the end of the hallway, his back to us. As the club members were filing by, the inmate turned over and sat up. "Dude!" he said. "Webb?" "What's up, Dude?" I held to the bars, looking at him. The rest of the boys filed past. Finally he said, "Hey, don't sweat it, man." He shrugged and smiled. "It sure beats the hell out of Vietnam." Then he lay back down and turned to the wall, and I never saw him again.

Astronauts have a special responsibility to the downtrodden of the earth. That's as much a part of being an astronaut as weightlessness or cosmic radiation. But the thing is, what will I say to people when they come to me for answers? What can I say that will help? Well, I guess I'll just have to keep my head on straight, keep my perspective. I'll say that one day we'll colonize the moon as a base for exploring other worlds. After all, our long-term mission as astronauts is to find new worlds for the human race to live in, because things here on earth just can't be fixed. Iris, Jane, Webb — if people like that are not part of the team, I'll say, then at least they should be proud to have known someone who is. It's no small thing to have known one of the men who can pave the way for people to follow, who can offer mankind hope. I'll tell them that each day of our lives is another day of training for the hard travels ahead. Every tough situation, every bump on the road, every hardship we encounter — it's all there for a reason; and if we work hard to keep a no-nonsense, can-do attitude, things will only be easier for us when life seems impossible somewhere down the road. I'll say that no matter what we choose to do with our time on this planet, we are trapped in a continuous process of development; we are all getting ready for something, something really big, whether we know it or not. In fact, it occurs to me now that, in a way, we are all training to be astronauts. Yeah, that's the kind of thing I'll tell them. They'll like that. It will put their minds at ease. [ From SPARKMAN IN THE SKY AND OTHER STORIES by Brian Griffin. Copyright (c) 1998 by Brian Griffin. Reprinted by permission of Sarabande Books ].

Back to Contents

|