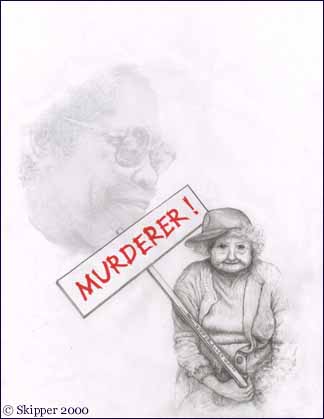

Now here's a story that never made much of a splash except in our town. It happened years before the civil-rights movement. But I tell you, it does prove that some people knew the difference between right and wrong where race is concerned even before all the hubbub. Sorry, I know hubbub isn't an appropriate term for the civil-rights movement. The movement was a wonderful thing. It had to happen sooner or later. You just can't treat people like animals and expect them to take it forever. Even though it was a hard time for lots of folks, in my opinion the civil-rights movement was long overdue. In fact, I even participated in it. But that's another story, and I'm getting way ahead of myself. So let me tell you about a small neighborhood uprising that happened not long after we women got the right to vote. Our neighborhood grocery store, where my family always shopped, was only two and a half blocks from our house. It was in a rectangular white building with a flat roof, located a block from the end of Main Street. Back then, Main Street was only 26 blocks long. Downtown started at about 10th Street and Main. From there shops, restaurants, two movie theaters, and a bunch of small businesses lined Main all the way past First Street to the river. From 10th to 26th Street were mostly houses, churches, and a few neighborhood concerns like Highbuckler's Grocery. Our grocer, Mr. Henry Highbuckler, was generally a trusting sort of person. Of course, there was really nothing not to trust in those days. Even though towns were growing and turning into cities, neighborhoods were still places where everyone pretty much knew each other and, for better or worse, knew each other's business. We'd get our groceries, sign for them, and pay at the end of each month. Lots of times I'd send one or two of the children to the store with a list. Henry would help them and always make sure what they bought was on my list. Nothing missing, and more importantly, nothing, like all-day suckers or bubble gum, added. He was, I thought, a decent God-fearing man we could all trust to do right by us. Our house was also less than a block from the Negro section of the city. Although there was a small grocery in that settlement, its shelves were only partially full. The old colored gentleman who ran it had a deuce of a time getting products from Southern white suppliers. Lots of the Negroes gardened, but it wasn't enough to adequately feed them and their children. I learned all of this from my friend Neva. So I talked to Mr. Highbuckler and he agreed to open his store to the Negroes for a couple of hours two evenings a week. In my naiveté, I thought it seemed like a good plan. Neva, her family, and friends were all thankful for my help. Surprisingly, no one in town raised a ruckus. We all just went about our business, and I forgot about the arrangement. Neva and I were just about the same age. We were both struggling to raise our children to be good, upstanding human beings. Both our husbands worked long, hard hours. Yet there was little left over at the end of the month for either family. We had a lot in common. One of the things we didn't have in common was race. Neva and I got to know each other one day when she was passing by, and I was working in my garden. The sun was beating down hotter than Hades. Neva stopped at the gate, watching me with her big, brown eagle eyes. I was so busy pulling weeds and sweating, I didn't notice her. "Missus, I'd be happy to help you for a bit," she stated flatly. I looked up and put my hand on my forehead, shielding my eyes from the beastly southern sun. At that moment I saw one of the loveliest smiles I've ever encountered in this world. That woman practically glowed from the sun reflecting off her ebony skin. I liked her, even loved her, from that first exchange. I saw that woman just about every day for the next 50 years. It wasn't until she fell over dead in her own garden one hot July day that our routine contacts ceased. I have to confess, I still talk to Neva at times. Guess what? She still gives me good advice, too. Now you probably do think I'm addled. Well, I'm not. People we love live on in our hearts and minds until we breathe our last breath and pass on to the Great Beyond. And if we really knew them, we can hear exactly what they would say in most nearly every situation. Pooh, I'm digressing. I'll get back on track now. Anyway, like I said, Neva offered to help with the weeding. I nodded my head ever so slightly. She opened our squeaky gate and came right on in. She wore a yellow dress with tiny blue flowers. A straw sunbonnet covered her jet-black crinkly hair pulled into a bun at the back of her neck. She pointed to my own straw bonnet lying on the ground at the end of a row of snap beans. "Best put that on Missus. Don't want you passing out on me." I did as I was told, smiling inwardly at her concern for my well being. With little conversation, we proceeded to weed that garden side-by-side. Both of us mopping our faces periodically to keep the perspiration out of our eyes. After about an hour and a half she said, "Name's Neva." I stood up, extended my hand, and responded, "I'm Maudie." She looked at my outstretched hand, shaking her head. "No ma'am, I'd best not do that. Don't want no trouble for either of us." Well, that started one of our passels of disagreements about the place of Negroes in relation to whites. Neva clearly accepted being relegated to a lower class. I thought she was nuts to accept such absurdity. She was right about one thing though. I didn't know what it meant to be black in the South back then. Of course, she didn't say it quite that way. But it was the one thing she was just a tad belligerent about. I still remember the first time I spontaneously hugged Neva. My Robert had been feeling poorly and Neva came to sit with him so I could walk downtown to pay monthly bills. Yep, that's the way we did it. No electronic automatic withdrawals or even mail in bill payments. We all went to each utility company every month to settle up. Neva came to the house with some of her herbs and natural remedies. Only the Good Lord knows what was in that stuff. Anyway, when I got home, Robert was sitting up for the first time in almost a week. He even had a bit of color in his face. Well, I just grabbed Neva and hugged her. I told her she was either an angel or a witch. She jumped back like somebody had slapped the tar out of her. "Missus Maudie, you got to be rememberin' that I's a Negro. You jest cain't go 'round huggin' me. If you're not careful, you gonna get us both in a heap o' trouble." Well, my dear, sweet Robert looked right at Neva and told her she was family to us and whatever happened inside our house was none of anybody else's blasted business. Neva gave a little grin and answered, "Yessa. But you need to make sho' she," looking at me, of course, "behave herself outside dis house." Robert threw back his head and laughed uproariously, "Neva, I hate to tell you this, but I cannot control one single thing that woman does. She's the most bull-headed, obstinate, determined individual God ever put in a dress." Well, Neva and Robert both had a good laugh at my expense. After that, things became a bit more relaxed and our friendship blossomed. But I have to tell you, Neva never would sit down to eat with us no matter how many times we asked her nor how much we all pleaded. I can still hear her saying, "tain't my place, Missus Maudie." One fine autumn day Neva and I had planned to do some canning for both of our families. We'd agreed to start first thing in the morning. When it got to be 9:30 and Neva still wasn't there, I got a bit worried. Finally, I headed down to Neva's house. I got a few stares that first time. A white woman alone in the area wasn't a common sight. When I knocked on Neva's door, I could hear her moaning. I went in and found her lying in the bathroom floor curled up holding her stomach. From the smell, I knew she'd been real sick. Her skin was ashen and clammy. It was obvious she badly needed a doctor. Home remedies wouldn't begin to deal with this. I guided and half-carried Neva to our house. Even I knew Dr. Fenton wasn't about to make a house call in 'colored town.' When he got to my house and saw Neva, he literally hissed, "You got me out here for this?" I stood my ground and he finally took a look at her. He concluded that Neva had food poisoning and that she'd either die or she wouldn't. I convinced him to write a prescription for me that I could have filled and then give to Neva. He didn't like it much, but, at least, he did it. Neva was luckier than some. She didn't die. She finally told me that she suspected Mr. Highbuckler was selling the colored's spoiled food. I felt like such a fool. I had been the one to ask for his help. Much to Neva's dismay, I showed up at the meeting her people were having at the Emmanuel Baptist Church. Initially, I sat in the back and held my tongue. Well, you know me. That didn't last long. They were just about to decide to try to live out of their gardens and get what they could from their own store, when I just couldn't keep still any longer. "How can you let him do this to you without a fight?" I pleaded. Well, the minister proceeded to let me know that if they said anything, they'd be receiving sheeted nighttime visitors. Their homes and their churches would be burned. And likely as not, some of them would be lynched, burned, or just shot. I started to protest. Then I remembered the nightmare of witnessing a young colored man being drug past our house when I was just a child. That poor fellow was lynched on Main Street because someone thought he had looked lasciviously at a white woman. I knew Neva and her friends weren't wrong. So I kept my mouth shut, but I couldn't stop my mind from spinning. My friend, Holly, also my favorite co-conspirator in the Women's Suffrage Movement, was dead, but the rest of us who'd only recently put away our Suffragist garments were still alive and kicking. We'd all seen the inside of the jail for one worthy cause, so I figured we should be up to another challenge. So, I proceeded to contact our little rebellious band. Only one of the group said that "Nigras ought to know their place" and refused to participate. The remaining six agreed that we needed to do something. It was Helen Sampson's idea. And what a fine idea it was. Helen's brother had gone north for work. He joined a union and was always writing home about their activities. Since we didn't work for the grocery, a strike was out. But Helen suggested a boycott. She told us how the workers up North made signs that told about abuses, then walked around peacefully in front of their company. They encouraged people not to do business with the company unless or until the situation was rectified. Course, we knew there had been some violence with some of the unions, but Helen was convinced it didn't have to turn out that way. When we adjourned that night, all six of us had unanimously agreed to make signs urging a boycott of Highbuckler's Grocery and saying exactly why. I wrote "MURDERER" in blood red letters on my sign. The next day we gathered as agreed at the end of Main Street. Signs held high, we marched together, shoulder to shoulder, the short block to Highbuckler's. We chanted such things as "Spoiled meat, tainted food. Today the Negroes, tomorrow YOU!" You see, we knew that if we didn't stress that whites could suffer the same fate, nothing would happen. We had to convince white people that they could become victims. We weren't altogether sure that was true. But if someone was so interested in making money that he'd sell food he knew was spoiled to coloreds, he just might decide to do the same thing to whites, especially to people he didn't particularly like. The first day we managed to stop a few folks from shopping at Highbuckler's, but most people just pushed right on past us. One fellow even called us "white trash". We didn't pay him any attention. We were back bright and early the next morning. That day a few more people turned away from Highbuckler's. The next closest grocery was about a mile and a half away and some decided the extra effort was better than having to face a bunch of rabid women. By the third day, the news of our boycott was getting around. Crazy old Bob Hatchfield was sent by our local newspaper to cover the ruckus. He'd done a real number on us when we disturbed the peace at the Governor's Mansion by chaining ourselves to the gates to protest not having the vote. We weren't expecting anything better and, needless to say, we weren't disappointed. I kept the boycott article, and I'll read some of it to you. Okay, here goes. "Six of the women who had the audacity to chain themselves to the gates of our Governor's Mansion during the suffrage movement are now marching around in support of Negroes. You'd think they'd have better things to do with their time. This community certainly does not need to be subjected to their outrageous signs and their more outrageous behavior. Whites here have always treated coloreds fairly. It is truly telling that there are no Negroes involved in proposing a boycott, only these already known-to-be meddlesome women. It is a sad day, indeed, when coloreds have more sense than white women. Of course, most of our readers will recall that the last shenanigans of this particular group of pesky women ended in their arrest. Too bad that hasn't happened this time as they, once again, demonstrate total disrespect for the traditions of our community." Well, I don't think I need to read you the whole darned thing. Reading even part of it is enough to make me want to slit my stretch marks. Much to Hatchfield's dismay, his article did something that old loon hadn't planned on. It got us more attention. The fifth day, which was the day the article came out in the morning paper, a group of local ministers, a priest, and our one rabbi came down and joined us. Almost nobody went into Highbuckler's Grocery. Late that afternoon, his rather mammoth belly proceeded the rest of him out the door. He held up his hands. "Okay, ladies and gentlemen." I think one of the reasons he finally came out was there were now men with us. Otherwise he'd have just kept on going out the back door at closing time. He knew we weren't foolish enough to be caught back in the alley. We kept our feet firmly marching on Main Street where all passersby could see us. At any rate, he went on to say, "the store will close at the regular time each day. I won't sell any more food to the Niggers." As he turned to reenter the store, we shouted almost in unison, "NO!" He hesitated for just an instant before turning to face us. His face was flushed and perspiration beaded on his upper lip. "What do you mean, no. I thought that's what you wanted. Now mind you, I do not believe for one minute that any of the food I sold was spoiled when I sold it. Those people are just too dumb to eat it before it goes bad. Now, however, I won't have to worry about the lies being spread about me because I will not sell to Niggers!" Helen, Beth, and I all stepped forward. I had a fleeting desire to swat that arrogant grocer over the head with my sign. Actually, it wasn't that fleeting. But I resisted the urge. Beth's voice was shaking as she informed Mr. Highbuckler that the colored people needed to be able to buy food that was safe and his grocery was the only fully-stocked grocery within walking distance for them. "Malnutrition," Beth stated, "is only slightly better than food poisoning. But in the end both can kill you." We all clapped and cheered. Highbuckler shook his head and said, "Well, I'm sorry. My mind is made up." Just as he was turning, a young man came forward. "Good evening, Mr. Highbuckler. Perhaps, this Sunday I can thank you and Mrs. Highbuckler from the pulpit for the consideration you show to all human beings. I think this is something the Good Lord would want from you. It is rare that any of us have so clear an opportunity to demonstrate our belief in the teachings of Jesus. You are truly blessed, Mr. Highbuckler." Well, that caught the old goat off guard. There wasn't much he could do or say with his own minister publicly giving him instructions. The minister tipped his hat, turned and left. I swear, if I hadn't been a confirmed, dyed-in-the-wool Methodist, I might have changed to Presbyterian that very day. Highbuckler whispered to the departing back, "They're not human". He didn't know I heard him. Then he gathered his wits and announced that he would be open to the coloreds two evenings a week and that all food products would be checked for freshness before being sold to anyone. We politely thanked him, lowered our signs and began to leave. I stayed just long enough to tell Henry Highbuckler that we would be regularly checking for any food poisoning among the residents of the Southeast Side, both white and colored. He turned a bit crimson, but I was pretty sure he wouldn't dare sell more spoiled food. Of course, Henry just had to have the last word. "You won this time, Maudie. But don't expect any favors from me. You and Mr. Roe get behind on your bills, and you can be sure I'm not carrying you for one single day." I knew he meant it, too. Later, when I told Robert, he just laughed and said, "Well, I guess we'd better make sure to pay our grocery bills on time." Neva and her people promised to let us know if there were any more cases of food poisoning that seemed to be related to the grocery. There never were again. So whatever else, I came to the conclusion that Mr. Highbuckler's word was good. He certainly was a bigot, but in the end at least he was a bigot who stuck to his promise. Well, you're probably thinking that Henry Highbuckler should have gone to jail. You're right, too. It just wouldn't have happened. We all knew that. Sometimes you just have to know what things you might be able to change and settle for that. Dianne Garner is the editor of the Journal of Women & Aging, The Haworth Press, Inc. New York/London and the editor of the Haworth Press Innovations in Feminist Studies book program. She is a former academic living in Key West, Fla.

Copyright © The Southerner 1999-2000. ISSN: 1527-3075

|