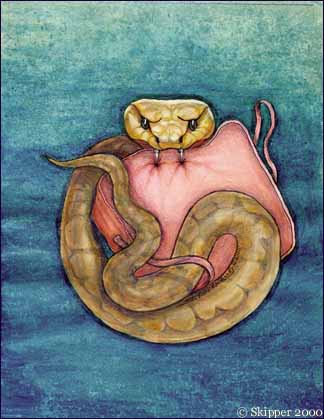

"Well honey," she tells me, "you can't very well not go at this point, because you've already accepted." She's talking around the pins in her mouth. They wiggle like mouse whiskers. "That was last month and this is now. I've changed my mind." We're up in her glassed-in sewing room that sails above the plum trees like a tiny barque forever tossed in a sea of green leaves. She's sewing me a blouse I'll never wear. "It's the Fourth of July," she says. "They're launching Glenn's new raft, and he and Sally will be devastated if you don't show up." She twirls me like a cotillion deb to attack the other sleeve. "I'm not going." "The whole family will be there." "He's not family yet," I say. "He's just her boyfriend." Sally's my cousin, orphaned by a drunk driver when she was eighteen. Mama took her under her wing and worries about her in equal measure to how she frets about all of us. Sally got herself a nursing degree and has always been highly skilled at taking care of her own life. At least I thought so until she starting dating Glenn, but now I'm not so sure. At a recent cookout in Mama's back yard Glenn followed me around until I squeezed in at the picnic table between my brothers, who complained but shifted good-naturedly to make room. However, while Sally was inside packing up their stuff he caught me sitting in Mama's car playing the radio. He slipped in quick and put his big paw on my thigh, asked in a thick whisper if I'd like to slip away some night and go out for a moonlight cruise with him on his raft. His molten-copper hair gleamed like a fallen angel's and his cerulean eyes were cloudy and sly. Sally works nights at the hospital. I blurted, "Are you crazy?" I jumped out and slammed the door. I zipped inside into my room and locked myself in. I watched through the blinds until they drove away. "If you don't come," Mama says, "it'll ruin the holiday for everyone." "Then y'all will all just have to sink without me." "Don't say that! Don't tempt fate!" "Who knows if his raft will even float?" I say. "He won it in a card game from a man in Itta Bena who built it in his carport." "Oh, it'll float all right. Glenn says it's made of steel and good cedar. He's tested it out in the lake." "I thought you disapproved of gambling." "I just want Sally to be happy!" "It'll sink like a stone with all souls aboard and I'll have to write the obit for the paper," I say. "I'm on that beat, you know — police beat, waterfront, and obits. The raft goes down, the story's mine on all three counts." "Now you stop that, Parrish." "I'll write a fine obituary: All the McCulloughs gone to a watery grave and I'm the sole survivor; in lieu of flowers send donations for my college fund." I work part-time on the Athena Times, putting money away for when I go off to college in the fall. I have three scholarship offers and am leaning towards Tulane. She bursts into tears. "I'm just kidding, Mama! Don't take it to heart." I pat her shoulder. She's always ladylike in her pastel summer dresses, unlike me in my tattered cotton shirts. When my brothers are ready to toss a shirt out is when it's soft enough for me. Her crying sends tremors through her body that I can feel in my palm. My going away is hard for her because I'm the youngest and the last. "I'll go," I say. "You will?" She peers up through teary eyes, brushing back silver hair with shaky hands. "Oh honey, you don't know what it means to me." She's darkened, and now she brightens like wild flowers shadowed by a summer storm that sweeps on past to become a tornado somewhere safely off in Alabama or Georgia. "No more talk about death and disasters, okay?" she says. She sets her lips into a valiant smile and looks bravely into my eyes. I manage not to laugh. Death has been her stock in trade since Daddy died. It's always, "Now when I die, I want you to have the la-la-la," never thinking that going on about her death just adds to the insecurity. "Mama," I warn her, "Don't push it." Too late now: We're on the raft, too far out to jump off and swim back to shore. Lake Chickasaw was a loop of the Mississippi until a deep-cut channel carried the river past and made an island across from downtown Athena. Sand piles up along the margins of the island and out in the lake making sand bars that come and go as the water builds and erases them. The best place for these is down close to where the lake becomes the river. Glenn's raft floated fine, even loaded with seven adults, four children and me. It slid out over the water from the marina like a giant rectangular swan churning up a steady wake. It made the willows on the island sweep past in a slow green blur, shivering in the sunlight. It pierced the still air and made breezes flow cool on my face. I hung onto the railing and looked ahead, splashed by spray tossed up from the prow and drinking in the pungent aroma of the lake. Sunlit waves dazzled my eyes. Sally slapped sandwiches together at a table in the shade of the yellow canopy where everyone was drinking soft drinks and beer, losing half their conversation to the muffled roar of the motor. Her auburn hair ruffled merrily in the buffeting wind and plucked red highlights from sun bouncing up off the water. Her face glowed and her eyes sparkled with a smile so happy it broke my heart. I leaned over and out to see if I could see my reflection below but all I saw was a distorted hollow shape sliding over the green-brown water. Looking down at it made me dizzy. The children careened around shrieking with excitement. My feet received the vibration of their pounding footsteps through the long rough cedar planks. Glenn had on a jaunty captain's hat. He drove and ignored me and I ignored him back. The raft was slanted up on a sweep of island sand next to another raft belonging to some of Sally's friends. People spilled out and mingled on blankets on the beach or perched in lawn chairs chatting, balancing plates of chicken and potato salad at precarious angles. The kids ran all over and started to light sparklers until they realized it wasn't dark enough to see them. Radio music floated up into the cottonwoods, alternating from rock n' roll to country-western and back again as competing factions slipped over and twisted the dial. At dark all the rafts and boats would gather back near the marina for the fireworks, joined by hundreds of cars parked sideways on the levee. But now in the sun a sandbar gleamed out in the lake and the kids clamored to swim out to it. Mama insisted they'd drown. "I forbid them to go unless an adult goes along!" she exclaimed, pointing one hand up into the air like the Queen Mother with her scepter. None of the parents wanted to leave the party, so the kids begged me to go with them and I said okay. I made certain all the younger ones had life jackets on, because close to the river the currents can be treacherous. For myself I decided just to bring along a boat cushion. The raft was empty. I dug into a gear chest and found a faded pink boat cushion. The cedar floor shifted to one side in the sand and I smelled the beer on Glenn's breath as he padded over and leaned in close. His shirt was hanging open. His belly was pale in contrast to his sun-darkened arms and face. He said, "I hear you're going off to Tulane. I could come down and look you up in New Orleans." He has a deep melodious voice that gets him any DJ job he cares to take. Is that what Sally fell for? I looked at Sally over in her lawn chair, Jackie-O sunglasses glinting in the bright light. Her eyes were hidden by the dark lenses. "Did you say something to me, Glenn?" I said. "Because I can't hear you, whatever it is. And you ought to think about what Sally would think if she heard you saying these things to me." He swayed his body lazily from the canopy support bars. "Oh," he said, "You're going to tell her? I don't think so. I just came to get another six-pack for the gang." But he glanced in her direction and shifted his eyes away. He dropped down like a panther and popped the lid on a built-in cooler. I heard him rummaging through the ice but I was already stepping away into the hot sand. My shadow flowed dark and sharp-edged beneath me. I felt a shakiness bubbling through my veins like water boiling in a percolator. Sally was laughing about something with Mama, who was shooing off a wasp with her straw hat, but it was like they were in a plastic bubble off in another world. I took the pink cushion down to the water where the kids splashed in the shallows and flung mud into the air. They hollered at me to hurry up. I shucked off the shorts and shirt covering my two-piece swimsuit at the last possible moment before sliding in and letting the water cover me. It was coffee-colored, silky and warm, with colder currents swirling deeper down. Goosebumps rose on my arms and my nipples hardened against my suit. I pushed the boat cushion ahead of me as I shepherded the laughing kids out into the deep water. Glenn's voice drifted out from behind us: "Y'all better watch out for the snakes! Watch out for nests of water moccasins!" A couple of the older kids snorted in derision but some of the younger ones were scared and swiveled their seal-sleek heads to me in the water: "Parrish?" "He's just teasing you," I said. "I won't let any snakes get you." But it was true that there were poisonous snakes in the lake. From a friend's dock I had witnessed a nest of baby water moccasins squirming around each other in a ball, drifting by in the murky water. Another time a copperhead went after our fish stringer that was hanging off the side of the boat. And I'd seen a five-foot long moccasin draped in a willow, its body the diameter of an orange. Growing up on the lake you heard lots of snake stories, like the one about the water skier who went down in a nest of moccasins, screaming and thrashing and sinking as the snakes struck him. I saw Glenn drop into his chair beside Sally. His scaring the kids made me angry, but it also amplified the nervousness I always felt swimming out here. If something was in the water you wouldn't be able to see it. Suspended silt made it go opaque, especially this close to the river. If a small fish nibbled on your foot it could be a shark for all you knew, lurking in the mud-colored water. I saw my father pouring cream into his coffee and joking that coffee and tea should be the color of the Mississippi River as it rolls past Athena. "If Daddy was alive, he'd kill him," I said. One of the kids dog-paddling near me turned and said, spitting water, "What?," but I shook my head and said "Nothing, honey, just talking to myself." The sand bar was an oasis of clean white sand lapped by waves and drenched with sun. I helped the kids make sandcastles. The lake smelled fresh and slowly I relaxed. It seemed like I was dissolving into the sand and the water and the sky, feeling it all swirl through me and take me to a state where there were no concerns about which college to choose or how I'd have enough money to make it through. I got lost with the children in their world, as if the lake and river carried all worries away and emptied them into the great blue sea I'd never seen down beyond New Orleans. The sun slanted away to the west and our shadows on the sand lengthened and rippled out across the golden-turning water. "Time to go back," I said. They argued because the castle complex we'd made was a thing of fairytale beauty and we all regretted having to relinquish it and knew that the lake would devour it. It seemed that such a splendid thing should last forever. But the kids were hungry and thirsty and eager to set off firecrackers. As we made our way back into the water the older boys ran back and stomped the castles down, howling with the joy of marauders while the little ones shrieked at them to stop and then joined in the laughter and excitement to see it all destroyed. The boys ran past us and dove ahead like otters plying the golden waves, splashing each other with great sweeping sprays of water. I let the kids go ahead of me. They splashed forward as I pushed the boat cushion beneath me and balanced on it. It held me up with my shoulders just above the surface and my legs hanging down. I swept my arms up and back through the water, progressing slowly after the children. The figures on the beach gradually got larger until the older boys were already streaking from the water shaking themselves like dogs as they ran up the packed sand. The little kids were still paddling along in their red and orange life jackets. I felt something wrap itself around my legs. It was big and muscular, twining itself around my dangling legs. I froze and could not move. I saw the children in front of me with their damp hair catching the glow of the sun like cherubs' halos and their arms and feet splashing forward. We were close enough to shore that I could catch snatches of talk and the scent of campfire smoke drifting out over the lake. My legs hung motionless in the grip of the giant snake and I couldn't breathe with the fear as though the snake also gripped my chest in its powerful coils. I couldn't see it because of the muddy water but my brain was computing, registering the size of the thing from how it coiled itself around my legs as if around the branches of a submerged tree. Its weight pulled me further down and the water almost reached my chin. The children moved in slow motion into the shallows. Some stood to run up onto the shore. Others were still in the water. No one looked back to see where I was. No one on shore noticed me. Abruptly I entered a deep state of calm. Somehow I transcended panic and moved through a transparent membrane to enter a small bright room where a familiar, light-blurred man and I surveyed the scene as if from a great distance. We wordlessly agreed that I must remain motionless to protect the children. Slowly, one... by... one... they reached the sand. Suddenly the snake uncoiled, as if it had done some calculating of its own and realized I was not a tree branch. As it released me I waited for one more moment. I envisioned its mouth only inches away from me still, the small glittering eyes and the sharp back-slant of its fangs. Then I launched off from the boat cushion, zooming forward through the water like a torpedo. I was running on the surface, flying on it until I reached the sand. "Is something the matter, honey?" Mama called. "I'm just fine," I said. My teeth chattered but my fingertips and toes felt as if they were on fire. I wrapped a towel around me and found a spot down the beach away from them all. I sat in the sand, shivering with shock until the sun warmed me and gradually coaxed my spirit back into my body. I saw the pink boat cushion drifting slowly towards the river. Mama came over with a plate full of picnic food and some iced tea. "Are you sure you're okay?" "Just fine." I watched her slog back through the sand. I took a bite of the potato salad and found I was famished. I ate all the food, down to the last crumb of chocolate cake. It tasted remarkably wonderful. The cushion winked out of sight in the sun-spangled waves. Glenn sauntered out of the woods up to me. He opened his mouth to say something, but I met his eyes and held my hand up like a traffic cop going "Stop!" I didn't say a word. As if against his will he closed his mouth and walked away. I took a nap. When I woke the shadows were purple across the golden sand and everyone was loading the raft to go. A strange sense of well-being surrounded me. Back near the marina as night fell, I gathered the little kids around me and watched the fireworks. The cascades of color that exploded and shimmered in the dark sky were a gigantic dragon twisting between stars and water, illuminating the heavens and dancing with his reflected twin in the black depths of the lake. Thunderclaps rolled across the water and echoed from the island's wall of trees, making the children scream with fear and joy. Weeks later I went out to cover a car wreck I'd picked up on the newsroom scanner. I arrived to find Glenn being loaded onto a stretcher, his car wrapped around a light pole and whiskey on his breath. The whole front end of the car was smashed inwards from the middle of its bumper in a sharp V-shape and the imprint of the pole made a neat columnar indentation on its crunched-up hood. "You told her, didn't you?" he snarled at me as I leaned over the stretcher. "I never meant it, you little bitch; I was just . . . " "I never told her a damn thing," I said. I walked away as the ambulance doors slammed shut. I had kept quiet because people can hate you for telling them a truth they don't want to know. Sally's deciding to let Glenn go might have had something to do with his drinking, or maybe it was just the way that people are brought together in life but stronger currents can sweep them apart. Going off shift one morning she met a handsome man in a Buick convertible, coming to take his mother home after an operation as Sally wheeled the lady to the curb, unaware she was about to meet her future husband. I go back in my mind to being in the water with the snake and I ponder it in my heart. I have kept it to myself. A strange sense of peace has stayed with me. I saw a news feature about near-death experiences and how people often come back with an expanded sense of who they are. They don't fear death anymore. It fits for me somehow. I wonder about the boat cushion. In my mind's eye I see it carried slowly southward in the river currents. Maybe it's hung up somewhere in willow branches or rotting in mud on the bank, but something tells me it's drifted on down past New Orleans and made it all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. I see it far below me when I think about it, as if I'm hovering way up in the silent winds far above. That's how I see it as I'm drifting off to sleep, a tiny pink square floating in the ocean, meandering along on its journey out into the waters of the world. Kate Betterton grew up in the Mississippi Delta and now makes her home in the Pacific Northwest, where she is working on a short story collection and a novel.

Copyright © The Southerner 1999-2000. ISSN: 1527-3075   |